This fascinating 1903 article from the French magazine Le Monde Illustré has good and bad points.

Its positive side: An eloquent journalist gives us a rare, vivid look inside the modernization of Jewish education in the Middle East more than a century ago. Its negative side: His biases. The author was a staunch colonialist whose writings bashed non-European cultures, exalted all things French, and reserved special scorn for Orthodox Jews and religion in general. Despite these shortcomings, the article contains great information and illustrations. It is therefore worth trudging through the rough bits, which are mostly near the beginning.

I first translated this for an English edition of Ángel Pulido’s book Sephardic Jews and the Spanish Language. That book abridges the article and omits most of the pictures, so I’m posting the full piece here with all the original images. Since it’s from 1903, expect a certain amount of now-dated terminology (“Oriental,” “Moslem,” sexist language, etc.).

THE FRENCH LANGUAGE IN THE EAST

The Educational Work of the Alliance Israélite

by Quercus

(Le monde illustré, April 11, 1903.

English translation ©2016 by Steven Capsuto.)

It looks best from a distance, in the great silence and vast peace of the desert: the silky Sea of Gennesaret, nestled mysteriously in a hollow among the iridescent mountains, dominated by the snowy cap of Mt. Hermon. The still surface of the water is an intense azure that holds your eye, and the pale-blue sky itself looks so deep that it could be another lake, stretched miraculously between the peaks.

Far below, the white, ramshackle buildings and the low domes and scraggy palm trees of Tiberias are a blurred speck on the tide-foamed coast. On bare rocks that bulge along the shores, the light casts indescribably magical decorations, unexpected chromatic contrasts, harsh notes, jarring tones that delight and disconcert.

But as we descend the steepening slopes toward the shabby town that hides behind crumbling towers and black basalt walls, not even the persistent magical light can help: neither the lake’s allure nor the sky’s radiant splendor can overcome the immense dreariness of the dilapidation and the ruins. Customs, traditions, beliefs: everything here is old, amid the unspeakable ancientness of all things Eastern. Like Jerusalem, like nearby Safed, Tiberias is a holy city in which the old persists and where Jewish particularism finds one of its last refuges. Aiming to be less vulnerable than in the Zion of the prophets, Jewish immigration brings ever-larger numbers back to this place. Even if nothing remains of the ancient Herodian city, the contours are there, perpetuated twenty centuries later by a race that lived its bravest hour here, a race that could easily have been crushed forever beneath the “harsh flatting-mill of the Roman world.”

Those who come to die in this necropolis tend to be stubborn obscurantists. Like their ancestors who rejected Greco-Latin thought, they resist our western culture by erecting a barrier of furious fanaticism and staunch distrust. The willful ignorance in which they bask is truly frightful. They are prisoners of the past, pinned down by the weight of tradition. They close ranks, cutting themselves off from the world, walled in by ritual, observance and the ghetto. Behold it in all its horror: the intolerant Judea of ages past!

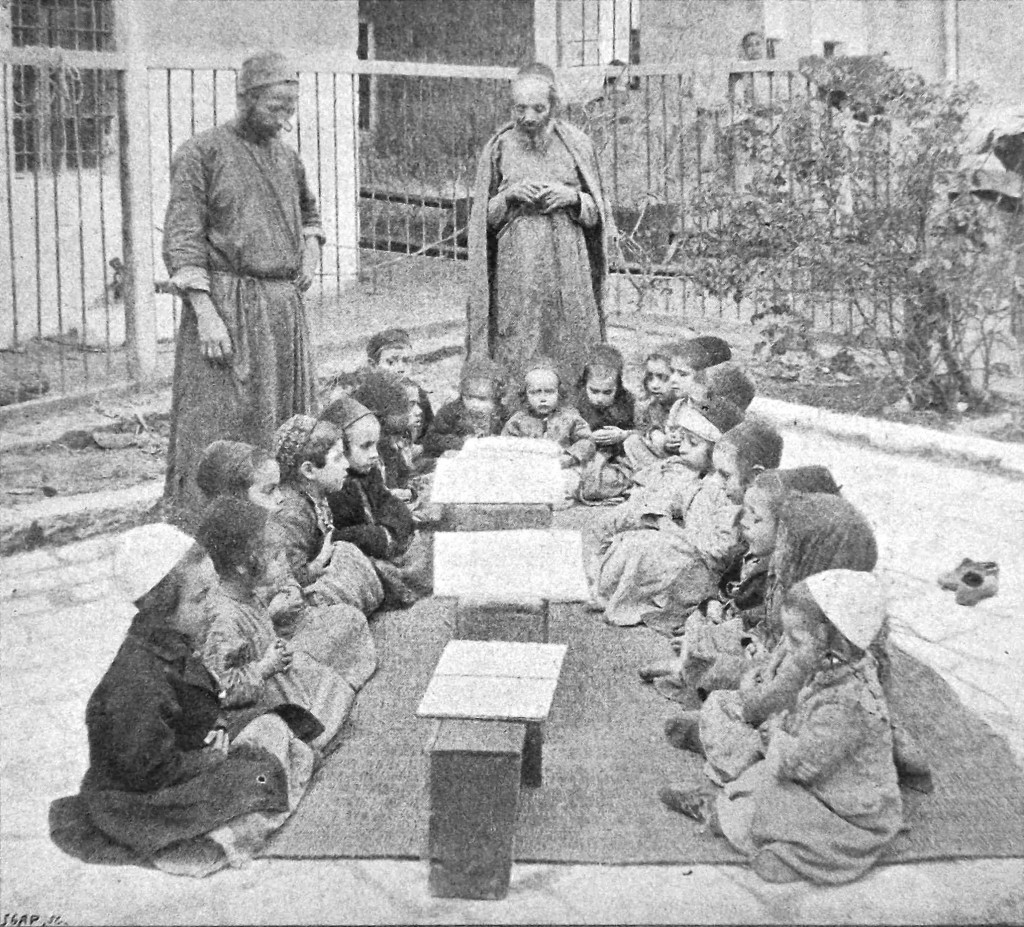

Nonetheless, in this anti-secular milieu, in this far-off Tiberias, isolated between two deserts and seemingly buried in the deep Jordan River basin, travelers now have the surprise of hearing our clear French syllables ring from the lips of children. In mazes of alleys where little white, cube-shaped Oriental homes squeeze irregularly into alveoli, and in covered bazaars where the acrid scent of spices mingles with the stench of the street, urchins swarm around, chirping our language as easily as they speak their own. This is because a few years ago, the Alliance Israélite Universelle founded a boys’ school and a girls’ school here, amid a mummified community. The Alliance modeled the schools on its other institutions in the East, and now we see the result of these first efforts. The boys’ school opened in 1897 and the girls’ in October 1900. Before that, Tiberias, like most communities in Palestine and Syria, had known nothing but Talmud-Torahs run by grimy rabbis, in which boys squatting on mats struggled to learn to decipher the Hebrew alphabet. Levantine towns are crawling with Talmud-Torahs, alongside countless prayer halls frequented devoutly by zealots of the Law. It is, in a way, the counterpart of the Arab madrasa, where poor youngsters, under a long stick held by a sheik, exhaust themselves by endlessly reciting suras from the Koran.

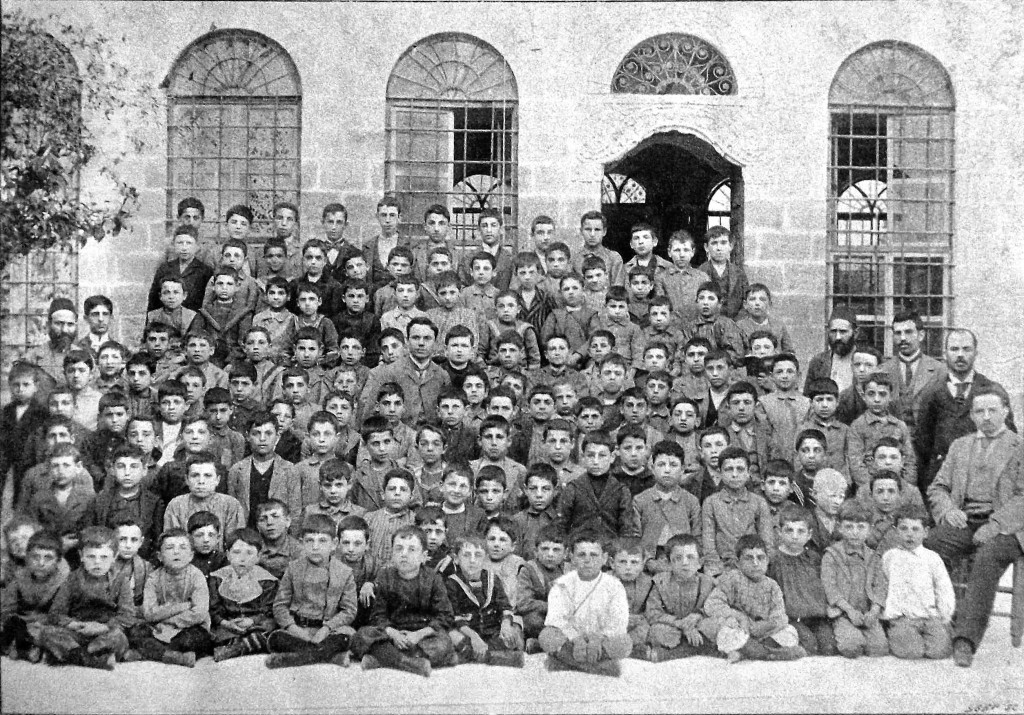

Creating schools in these environments, which meant colliding head-first with entrenched religious prejudices, seemed the most chimerical of enterprises twenty years ago. Nearly everywhere, the rabbi excommunicated the educator, the apikoros, and his impure knowledge. The fight went on, but the breach had been made and school triumphed decisively over synagogue. We can assess the resulting intellectual improvement, for which our French language was the effective tool, simply by walking through any Alliance school and then, as a point of contrast, visiting the best-run Talmud-Torah. Readers who compare the two photographs printed here—the old-fashioned school and the modern one—will see the unmistakable difference.

Talmud-Torah: old-style Jewish primary school

Modern School: one of the Alliance Israélite schools

Sometimes, teachers have had to work absolute wonders to do their job. In Tiberias, for instance, the headmaster, Mr. Hochberg, found the whole population roused against him by the rabbis, and had to promise the families not to teach anything but Hebrew. He made a kind of truce with the least inflexible locals, and a nucleus of students developed. The school did, in fact, teach Hebrew, but it served as a vehicle for other subjects in the curriculum. This experienced, admirably patient educator strove to awaken the children’s minds gradually, to instill the desire to learn. The Hebrew lesson became a science course, a history course, a moral philosophy course. And then one day, while discussing history, he spoke to them about France, of her deeds in the world, of her language, which is that of Europe’s cultured elite, the true language of civilization. A useful language in Syria, where it is spoken in all the large coastal cities. And he announced that if any student wanted French lessons, he would give them for free in the evenings, after class, on his own time. At first, just one student ventured to attend, then two, then three, then a proper small class, who were soon envied as a privileged group. And finally, even the parents, who were Sephardim (Spanish Jews), came to ask the teacher to give their children French lessons. Thus Talmudic rigidity began to bend. The school introduced a regular course in its first division and, little by little, over several months, French became the language of instruction in all subjects except, of course, religious studies, entrusted to a rabbi. That is the system used in all Alliance schools. They won the battle so thoroughly that when the girls’ school opened three years later, the families put up no resistance: from the first day, the headmistress and teachers used only French.

I asked questions while visiting this little world. Not only did the children understand all my queries, but the accuracy and confidence of their answers were striking. How proud they all were to show a Frenchman the progress they had made! They vied to see who would raise a hand to go to the blackboard, the terrible blackboard that our Western pupils too often consider an instrument of torture.

The classroom facilities are well designed: well-ventilated rooms whose walls bear maps, natural-history pictures and all manner of special illustrations that, like the books placed in the children’s hands, come from our best-known Parisian publishing houses. Of the 120 boys who attend this school, 70 eat lunch there. To give them a taste for working the land, the headmaster teaches a basic gardening course, complemented by practical sessions on a plot of ground rented for this purpose. The best students go on to the vocational school in Jerusalem or to the Mikveh Agricultural School. Others are apprenticed to artisans: coppersmiths, blacksmiths, saddlers, wheelwrights, carpenters, etc., etc., whom the Alliance pays a small sum to train them. And so the effort continues: French thus moves from classroom to workshop, and this manual labor is meant to round out the intellectual and moral education begun at the school.

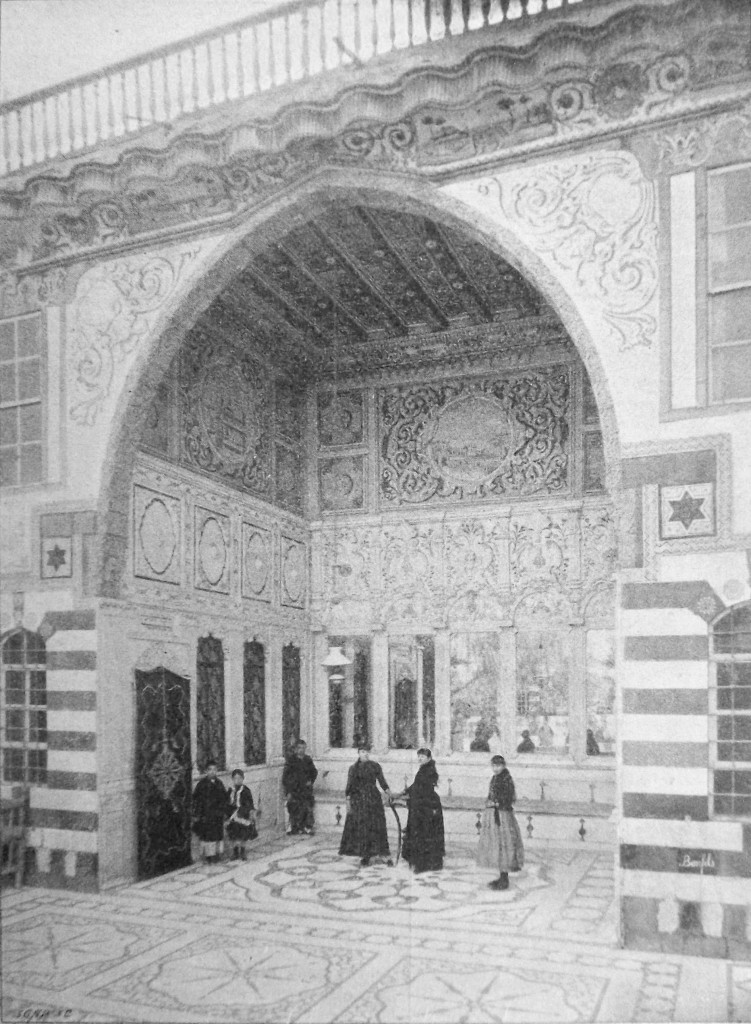

Patio of the Jewish girls’ school, Damascus, Syria

Though newer, the girls’ school already has 200 students. Combined with the enrollment of the boys’ school, that makes 320 pupils out of Tiberias’ 4,000 Jewish residents, a very large percentage.

The girls’ school is in a separate, very well laid out building. All classrooms open into an interior covered gallery in the Moorish style, and the windows face the lake. The most pleasant, sunny room is reserved for the littlest girls, out of health concerns for which the young, intelligent headmistress cannot be praised enough. About eighty little girls, the poorest, use the canteen, where they receive a hot meal at midday. The curriculum is the same as at the boys’ school. Their manual apprenticeship is in sewing. All the little girls are extremely diligent: the worst punishment that can be imposed on those who neglect the rules of cleanliness is to send them home for a day. You should see how immaculate they are and what a contrast they are from the other children of Tiberias, whose eyes and noses are too often nests for flies. They already reflect the happy influence of their education. Curiously, it seems these little curly heads contain more independence than is seen in the boys. The girls whom I asked about arithmetic, for instance, did not hesitate to draw the + sign, a cross, while at the boys’ school they replace it with an inverted T: ┴ . I do think a thin voice whispered, “It’s a sin.” But so timidly!

These childish reactions show how petty and low the primitive fanaticism of these lands can be. In this regard, I should note that of the two elements that make up the Jewish populace—the Ashkenazim, of German, Polish or Russian descent, and the Sephardim, who came to the East after their expulsion from Spain—it is the latter who, practically all by themselves, make up the Alliance’s entire school population in Palestine and Syria.

I cite the schools of Tiberias as an example because they are the newest and were set up in an environment unhospitable to our language and to the educational successes that flow in every way from our French methods. In towns less isolated and less closed to outside influence, the results are marvelous. I visited the schools in Jerusalem, Jaffa, Haifa, Beirut, Damascus, etc., etc., and can state that everywhere, the work of the Alliance Israélite remains unrivaled in its structure, the quality of its staff, and the education it provides. This sentiment is shared by all impartial travelers directly or indirectly concerned with the question.

The Alliance schools in Jerusalem have the largest enrollment in that city. They have huge new buildings with space for up to five hundred students, and a vocational school that I shall discuss shortly, the only institution of its kind in Palestine. Here as elsewhere, what is remarkable is how fluently the children speak our language. In their mouths, French ceases to be a foreign tongue: they have assimilated it completely and talk it with stunning ease of diction. They use it constantly, not only in class and at recess but on the streets. They read books only in French, and one can say they have a French mentality. They love France wholeheartedly, know her history, especially her modern history, whose milestones include the emancipation of their race. I have seen fifteen-year-olds become choked up, their eyes wet with tears, at the mention of our country’s glorious battles against old Europe for the triumph of justice, toleration and liberty. This is precious because it indicates plainly the spirit of the education they receive, their intellectual training, thanks to distinguished educators such as Mr. Calmy, whom I must commend for his skill, enlightened dedication and impeccably sound methods.

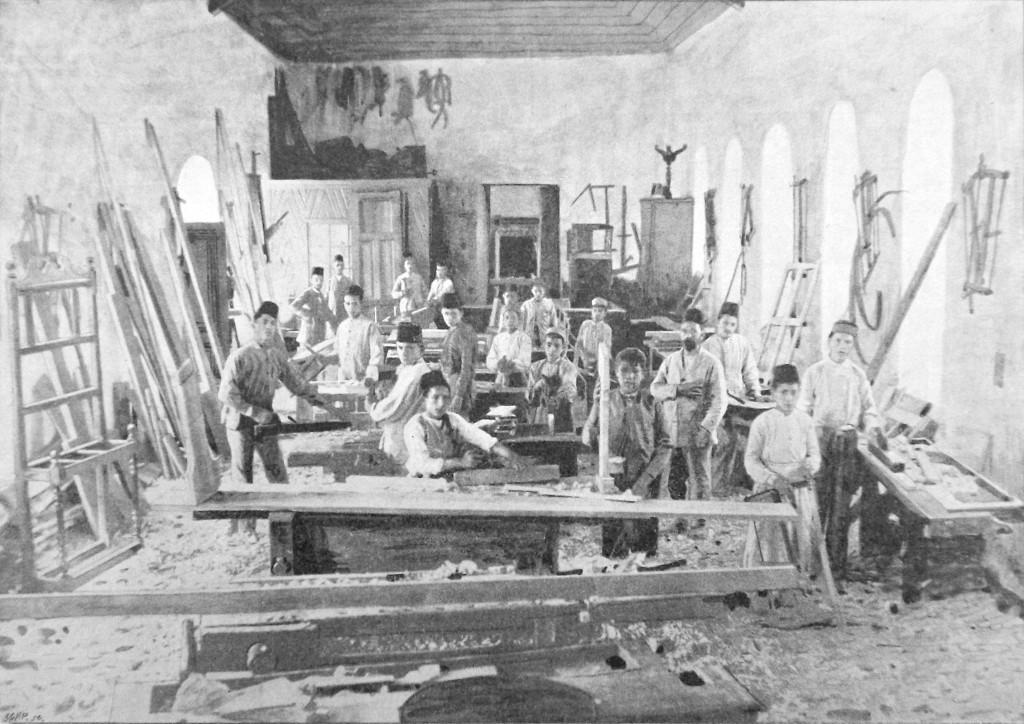

Jerusalem Vocational School: Carpentry Shop

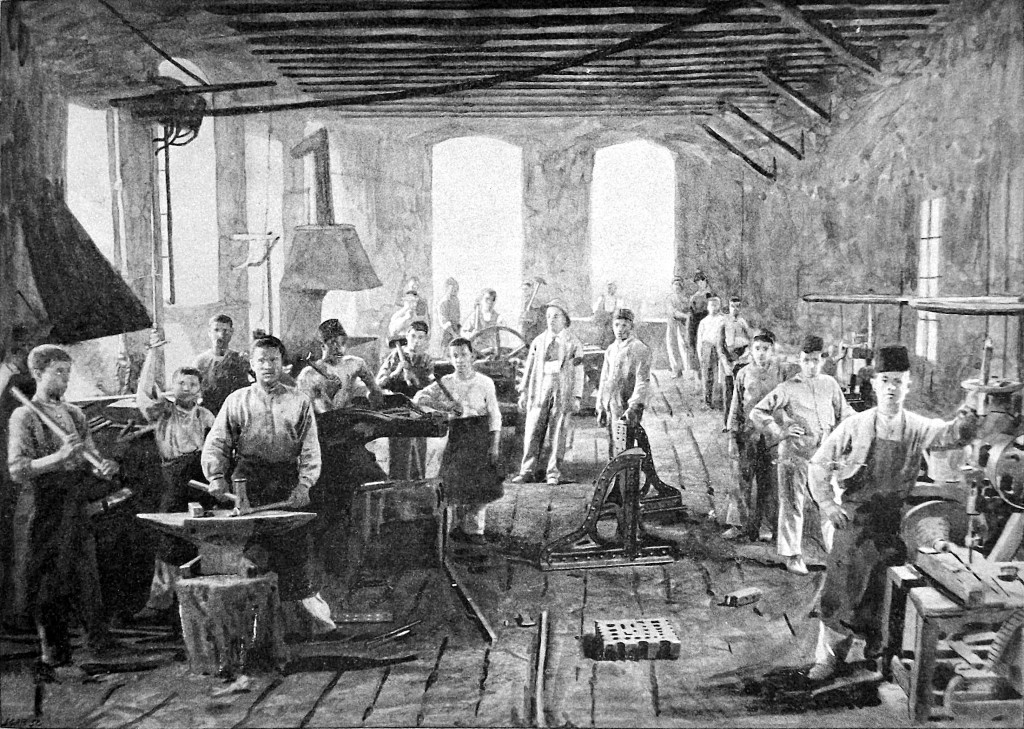

Jerusalem Vocational School: The Forge

Regrettably, there is no longer a Jewish French school for girls in Jerusalem. Many girls have left the English school, as they only want to learn French, and they search in vain for teachers. One hopes this gap will be filled and that there will be absolute equality of the two sexes.

Such equality does exist in the other cities in Palestine and Syria. In Haifa, for instance, the girls’ school is on the same premises as the boys’ school, and by the upper years these girls have acquired a purity of pronunciation that completely astonished me. This establishment, serving a hundred students, is overseen by Miss Delfour,[1] a refined, distinguished young Parisian Jewess, from whom the children acquire diction that successfully sets aside the French patois that too often grates on the ears in this country. I had them read difficult passages of prose or verse from an anthology, and they got through it wonderfully. It should be noted, though, that the girls everywhere have clearer, purer pronunciation than the boys. Of the latter, 191 attend the school in Haifa directed by Mr. Benchimol, whose lapels blossom with medals from the French government for his service to education.

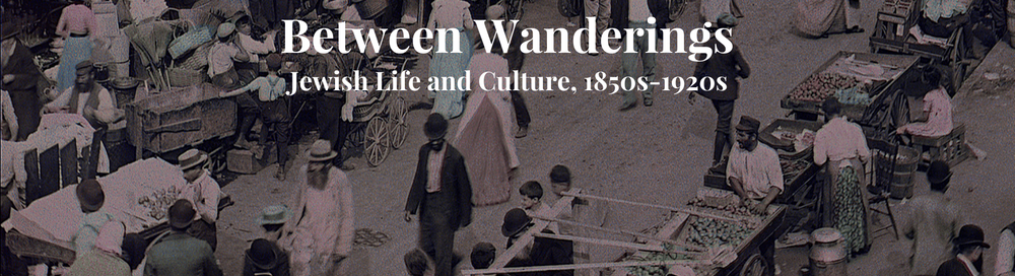

Along this Asian coastline, from the Sea of Marmora to the outermost bounds of Palestine, the Alliance Israélite has twenty-eight clusters of schools that teach some six thousand children in total. If we include comparable establishments in Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Tripolitania, Egypt, European Turkey, Bulgaria and Persia, the elementary schools alone number 112, educating more than thirty thousand students at an annual expense of almost 1.2 million francs, paid entirely by the Alliance. This vast educational enterprise, from which France’s cultural influence profits considerably, does not, in fact, cost a single centime from our national budget. That detail is worth emphasizing.

Although these schools were founded specifically for the Jewish communities, their doors are fully open to children of other faiths. Seated side by side with Jewish classmates, one finds Moslem, Greek Orthodox and sometimes Druse children, as in Haifa, where no fewer than thirty-five non-Jews attend the boys’ school. It is to the teachers’ credit that no proselytizing occurs inside or outside the classroom. This is an absolutely exceptional, very happy example in a country where racial antagonisms and religious hatreds are, as a tactical matter, expertly maintained and developed.

After graduation, the alumni have a role to play through private initiatives. Alliance alumni associations are proliferating, and some are very prosperous. The association in Smyrna, for instance, can already donate three hundred francs to fund the popular evening courses in that city. These organizations generally have a library and reading room that, besides the Alliance’s regular publications, receive several Paris newspapers and some French magazines. There are periodic lectures and also theatrical performances that invariably draw on our classical or modern repertoire.

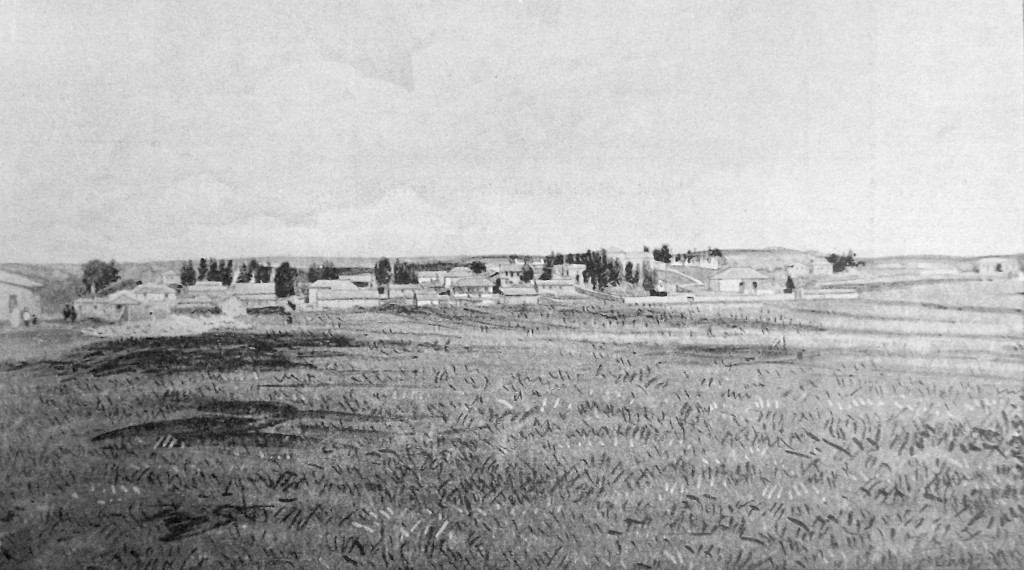

Panorama of the Mikveh Agricultural School, near Jaffa

The Alliance recruits its teachers from these same Eastern schools. Each year, the best students compete to go to the Jewish Teachers’ College in Paris. Young women earn their certificate at three private boarding schools, where, like the young men at the Oriental Teachers’ College, they receive instruction from French university faculty. In both cases, the curriculum is meant to prepare them for the advanced professional diploma, which most Alliance teachers now hold.

This ensures an absolutely consistent faculty. Uniform teacher training; uniform curricula, methods and spirit; in short, a unity of management from a central administration in Paris. It is the source of the unimpeachable superiority of the Alliance Israélite schools over all similar establishments.

I have kept the foregoing summary brief, since an exhaustive treatment would require a detailed, overly long monograph. It remains for me to say a word, now, about the two prototypes that are the Alliance’s crowning achievements: its Vocational School in Jerusalem and the Mikveh Agricultural School near Jaffa.

The Jerusalem Vocational School is thriving today under the technical direction of a graduate from our Châlons School of Applied Arts and Crafts. Here the young are passionate about manual labor and understand its grandeur and beauty. Behold the man of the new generation, the Jewish laborer at last, clad in a leather apron, face blackened, chest exposed, sleeves rolled up over well-muscled arms. Such a fine replacement for the pitiful figures of the ghetto, the Biblical curled sidelocks, the hideous fur caps and the antediluvian long coats! The busiest workshops are the blacksmith shops: they employ thirty-seven apprentices supervised by a French foreman. The carpentry shop has twenty-six apprentices, the coppersmith shop twenty-one, the sculpture and woodcarving shop thirteen. Those are followed by stonecutters, woodturners, cabinetmakers, cartwrights, saddlers, etc., and finally the weaving workshops, where mostly Yemenites work. The sculpture and carving section is of particular interest. It is entrusted to Mr. Ben-Sion, an artist of merit who studied at our Paris School of Fine Arts.

Of the 115 students, 68 live on the premises. After their apprenticeship, they return to their country of origin or move to one of the big cities along the coast, where their specialty can guarantee them work. Teachers from the elementary school tutor the student apprentices each evening. This remarkable institution’s general operating costs total 125,000 francs per year, minus about 48,000 francs in revenue from the workshops’ products. The Alliance makes up the deficit of 77,000 francs.

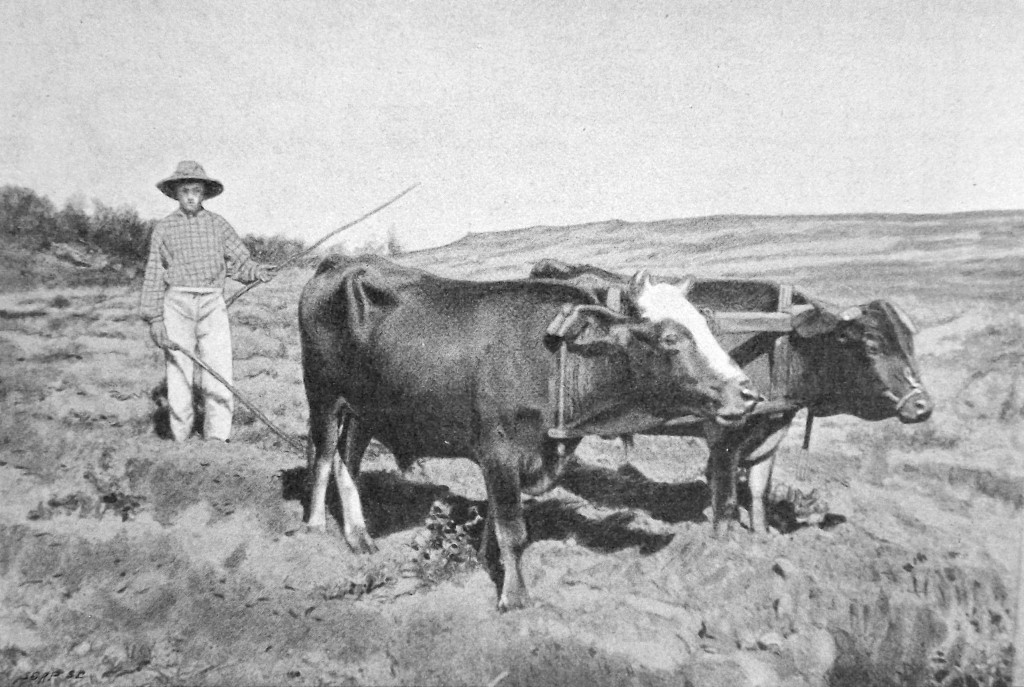

Mikveh Agricultural School: Central Walkway

Mikveh Agricultural School: The Nursery

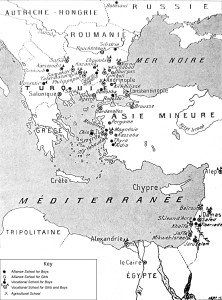

The Mikveh Agricultural School was founded in 1870, patterned after France’s écoles pratiques.[2] Its goal is not to produce specialists but colonists. Given the subjects it teaches and the nature of the courses, it can be considered an institution of higher learning. The program lasts five years, of which the first three are devoted mainly to theoretical instruction. In the final two years, students primarily do practical work, with lectures in the evening. No fewer than two hundred students live at the school. Like the director, Mr. Niégo, who is an excellent administrator, all the faculty he has brought together are graduates of our agricultural colleges: Montpellier, Versailles or Grignon. It is such a center of French influence that our language is even beginning to spread among the Arabs in the vicinity.

In 1870, this entire Plain of Sharon was nothing but sandy desert, but now it is a magnificent oasis, visited regularly by travelers passing through Jaffa. It is practical proof of the country’s latent natural riches, which can be developed everywhere through European scientific techniques.

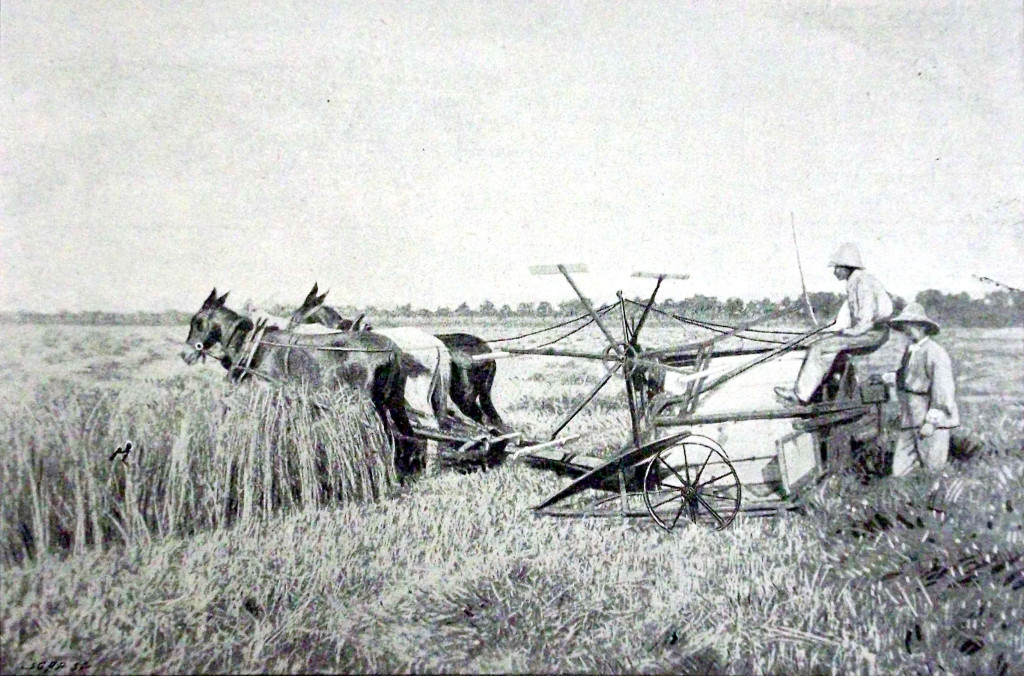

Intellectually and physically, everything here bears the mark of France. The books and tools come from France. The most advanced farm equipment systems—plows, mechanical mowers and reapers, reaper-binders, motorized threshers, etc.—are all made in our country. The French brand is also on the hand implements, supplies, hides, cloth, etc. Laboratory chemicals, groceries, fabric for students’ clothing, hosiery, etc., are dispatched by French firms.

Like all Alliance establishments, it has a library consisting almost entirely of French works. Here is a random sampling of the authors whose works I found in students’ hands during my visit to Mikveh: Corneille, Racine, Lamartine, Balzac, Flaubert, Sully-Prudhomme, Daudet, Loti, Bourget, Zola. Among the young people whom I questioned about their reading, I found a very well-developed literary judgment.

Upon graduation, the students are placed in Jewish colonies in Palestine or Syria as head gardeners, administrators or senior husbandrymen. Others are sent to colonies in Cyprus or Smyrna, or to farming settlements in Judea, Samaria or the Galilee. Those with the best grades go to the National Agricultural Institute in Paris, where they sit in on classes. During their stay, they reside at the Jewish Teachers’ College in Auteuil.

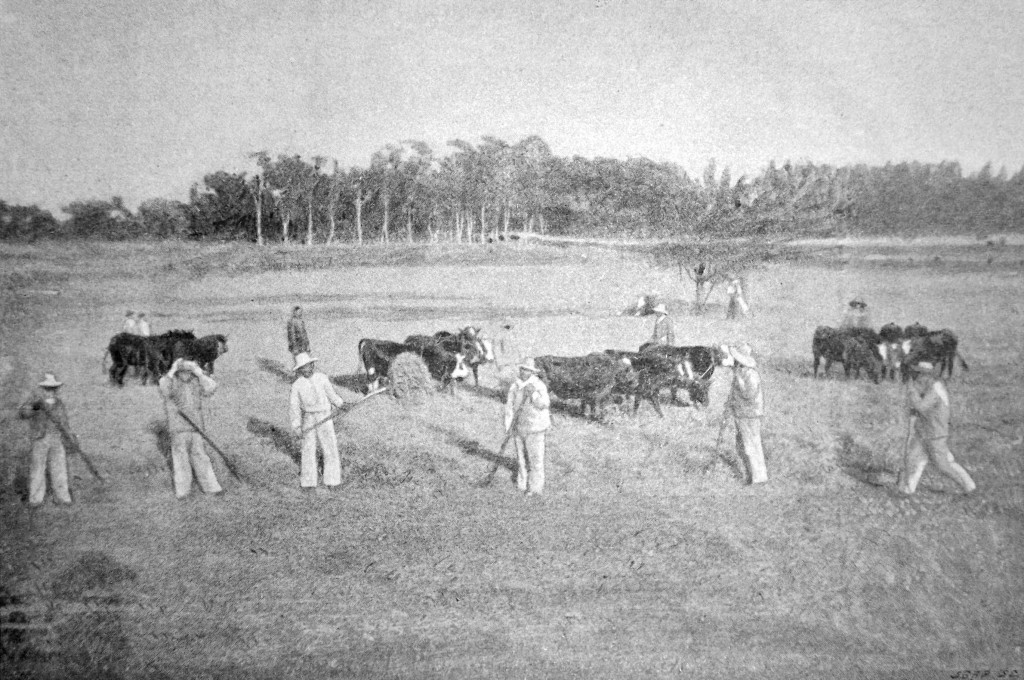

Mikveh Agricultural School: drying grain in the field

Mikveh therefore grows and nurtures an elite youth with strong intellectual ties to France. While working toward its defined goal, the institution also happens to help maintain our cultural supremacy over the peoples of the Orient. Moreover, our consular agents in Palestine, who are no fools, have never shown the slightest sign of practical appreciation toward the School’s staff or the School itself.

One more important detail: to date, the Mikveh School has cost fully a million francs, which includes, it is true, the price of the land, buildings, equipment, etc. The annual expenses total 163,000 francs, and working the land produces revenue of about 65,000 francs. That leaves a deficit of 98,000, covered by the Alliance.

Mikveh Agricultural School: mechanical mower

Mikveh Agricultural School: threshing machine

In short, then, Jewish educational work in Palestine, Syria and Asia Minor has three facets: 1) primary schools and apprenticeships; 2) a vocational school of arts and crafts; 3) an agricultural college. There is a whole series of coordinated efforts, and it would be impolitic and unfair to ignore them. In a recent article in the Revue des Deux-Mondes (the first issue for March), Mr. Anatole Leroy-Beaulieu, while calling the Jewish schools “one of the sturdy boughs from which the teaching of French branches across the East,” frames his homage in these terms: “In Eastern Europe, Asia, Africa and throughout the Mediterranean, the Alliance Israélite Universelle performs services to the French language that our patriotism should be able to appreciate, but which sectarian minds cannot recognize.”[3]

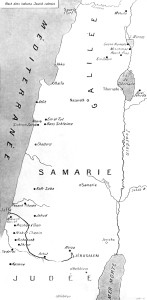

The Alliance’s educational work is not, however, the only thing the Jewish world has done in the Levant. There has also been a strong economic impetus for several reasons, especially since the influx of Russian Jews into Palestine. I wish to speak of these ongoing colonization endeavors that, thanks to massive French capital, have spread some twenty farming communities from the plains of Ashkelon to the mountainous regions of central Syria. This return to the land for the physical and intellectual uplift of the race has left a forceful imprint on the progress of Jewish thought over the last twenty-five years. The three groups of colonies—Palestine, Samaria and Galilee—have settled a population of five thousand souls on this soil. Other settlements are forming in the Trans-Jordan region, near the Haouran, where vast swaths of land have recently been acquired. We find these efforts all the more interesting as they are the only attempts thus far to counter the German colonization efforts. I visited the largest agricultural colonies and was astounded at the determination, labor and courage it took all these pioneers to realize their dream. In the scorching sand and on once-bare rocks, there now grow vines and trees. Fields of grain wave as far as the eye can see in a place where before, even thickets would not creep. Marshes were drained to stem the fevers that had carried off whole families. They have dug wells, built canals and erected villages that, amid the arid surroundings, are true havens of greenery. Schools, libraries, lecture halls, elected municipal governments: it is European life flowering in the middle of the desert.

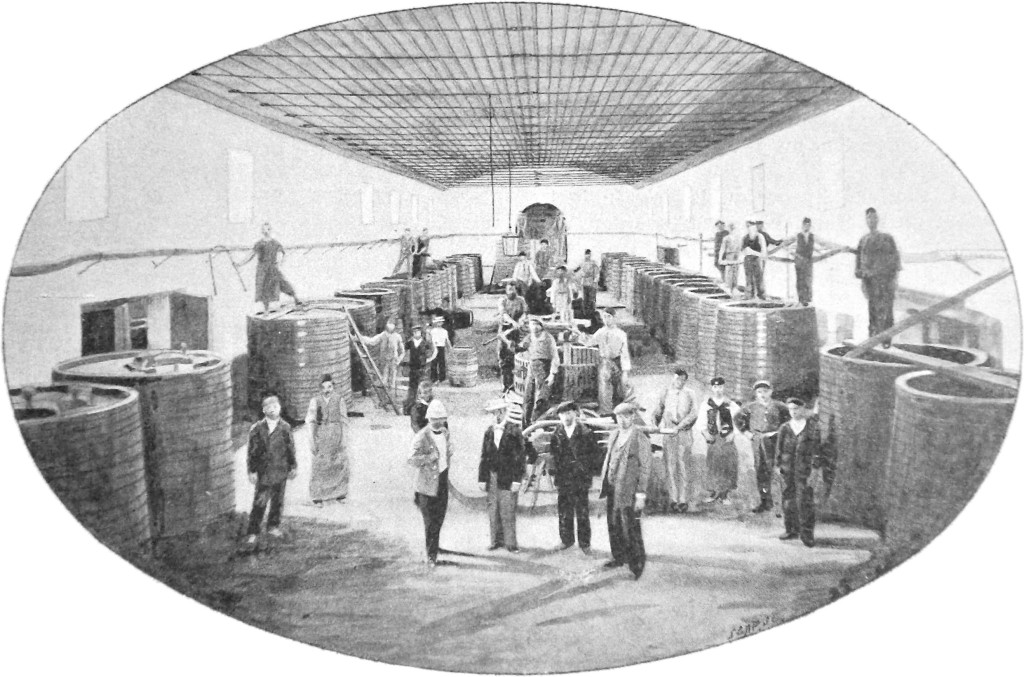

The Jewish colonists have succeeded mainly as wine-growers. With the aid of plans from Bordeaux, they have set up magnificent vineyards that yield a superior wine.

The layout of their cellar at Rishon-le-Zion was more or less copied from the Girondin system. A grave crisis, overproduction and sales at a loss, led to a necessary response: the colonists are now expanding their efforts into large-scale farming and into raising livestock.

The agricultural colonies – Mishmar Hayarden

Whatever happens, they are a force to reckon with from now on. In their transformation, the Jews are casting off their shackles, taking on a modern appearance and mentality, and, more and better than some others, they can serve as a link between Europe and the East. They have already introduced a new type of agriculture here, and they are likely to bring industry to the region as well. Our rivals understand this, no doubt, as this clientele, which is very much ours, is being fought over bitterly.

All of England’s propaganda or would-be propaganda is directed at the Jewish element, but with an eye to religious proselytizing that, very fortunately, limits its effects.[4]

Germany, despite the anti-Semitism it exhibits at home, delights in the promises its emperor made to the Zionist delegation during his journey to the Holy Land. Could there have been more than promises, since, at the Zionist Congresses in Basel, there was majority support for motions recognizing the German sovereign? On this topic, let us say that the Zionists are the Alliance’s adversaries for reasons that cannot concern us, as they relate to the inner aspects of Jewish life.

Lastly, Russia, which decreed stern measures against its subjects of the Mosaic faith and corralled them into Bessarabia and along Russia’s western border, has now ordered its consuls general to extend its protection to all Russian Jews in Palestine and Syria—protection most of them would gladly do without.

Let us not forget, though, that these Russian Jews make up most of the population of the agricultural colonies, founded with French capital and run by a French administration.

That suffices to show us what policies to pursue and what role to play.

Translator’s notes

[1] Historical staff records on the website of the AIU’s archives give her name as Alice Dufour, not Delfour. Source: website of the Alliance Israélite Universelle archives (in French).

[2] At the time, France’s agricultural Practical Schools taught basic and intermediate farming skills, mixing classroom instruction with hands-on experience.

[3] These quotations are from Anatole Leroy-Beaulieu’s article “Les congrégations religieuses: le protectorat catholique et l’influence française au dehors,” Revue des Deux Mondes, March 1, 1903, 70–113. The Between Wanderings book series has published a new translation of Leroy-Beaulieu’s 1904 lecture “Jewish Immigrants and Judaism in the United States” as a photo-illustrated booklet called Jewish Immigrants in Early 1900s America: A Visitor’s Account.

[4] Quercus was writing at a time when European colonial powers were competing for cultural and commercial dominance over the Middle East. In the previous paragraph, he says that France is winning the fight (Middle Eastern people are “this clientele, which is very much ours”). He knows that Britain, too, is courting the Jews of Palestine, but he thinks the British will undermine their own efforts by trying to convert people to Christianity, thus alienating the Jews.

NEXT WEEK’S POST: “Proto-bat mizvahs” in 19th-century Italy.

![The agricultural colonies - Kastinia [Translator's Note: Now Be'er Toviya]](https://betweenwanderings.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Graphic15-Kastinia_DxOVP_ret-1024x483.jpg)