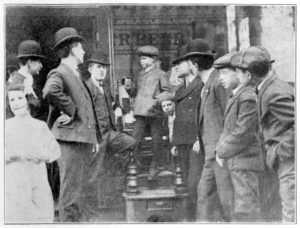

New York’s first purpose-built Yiddish theater, the Grand, opened in 1903 and was bought by actor–producer Jacob Adler in 1904. While the People’s Theatre nearby was staging popular fare, Adler’s Grand Theatre often presented literary plays ranging from Shakespeare to the modern realist dramas of Jacob Gordin. [Photo from the book Jewish Immigrants in Early 1900s America: A Visitor’s Account.]

Today’s “guest blogger” from the past is a reporter for the Washington, D.C. Evening Star who wrote a feature in 1906 about foreign-language theaters in New York. In the excerpts below, the anonymous writer describes the plays and ambiance at three well-known Yiddish theaters of that era: the People’s, the Kalich (formerly the Windsor), and the Grand.

Except as noted, the photos and captions are not from the original article. Future posts about Yiddish theater will look at sources that are more specifically Jewish, but this colorful “mainstream” article, with its you-are-there feel, seemed like a good starting point.

It is conceivable the writer might be exaggerating slightly. (Did almost every production at the Grand really end after midnight?) But most of the information matches what I have read in Jewish materials, right down to the prompters at certain theaters who would read the whole script aloud during performances to remind the actors of their lines.

QUEER PLAYHOUSES

in New York That Are Patronized by Aliens

PLAYS IN FOREIGN TONGUES

Nightly Delight of Audiences of Different Nationalities

LEADING JEWISH THEATER

Where Dramas by Suderman

and Hauptman are Given Long

Before they Appear on Broadway

(Evening Star, March 10, 1906)

[The People’s:]

…In the very heart of the Bowery stands the People’s Theater, large and pretentious, with signs in Yiddish which proclaim that a melodrama is going on within. The place is always crowded, and there is no fashionable lateness about its audiences. They scramble in as soon as the doors are open. Stout matrons with children at their heels, pretty, dark-eyed Jewesses, long-bearded patriarchs, vegetable venders, ol’ clothes men—they are all there, they and their families. It is a good-natured, animated crowd. As the theater fills there is a hum, then a buzz, and presently the gallery begins shouting and stamping its impatience.

Bessie Thomashefsky—half of the famous Yiddish theatrical couple of Boris and Bessie Thomashefsky—was beloved for her performances in musicals and comedies at the People’s Theatre. Here she plays the title roles in Dos Grine Vaybl, oder Der Yidisher Yenki-Dudl (The Greenhorn Wife, or The Jewish Yankee Doodle) and Der Griner Bokher (The Greenhorn Boy), both from 1905. [Photos and caption from the Jewish Immigrants book.]

The melodramas offered are like our own thrillers of the “Two Little Vagrants” order, but the scenery and costumes are Continue reading