Our “guest blogger from the past” is a 1920s reporter for the Jewish Daily Forward (the Forverts). By 1923, the article says, many assimilated Jews in New York City didn’t want neighbors to know they were Jewish, and so they began ordering Passover foods from department stores instead of Jewish small businesses.

Why? Well, a delivery boy in Lower East Side garb would have been a giveaway, but a Macy’s delivery van, they figured, was “neutral.” This is my (quick) translation from the original Yiddish.

The Forverts, March 29, 1923

They Buy Their Matzos from Gimbels and Macy’s Department Stores

Newly rich “all-rightniks” don’t want Christian neighbors to see East Side Jews delivering packages to them on Pesach.

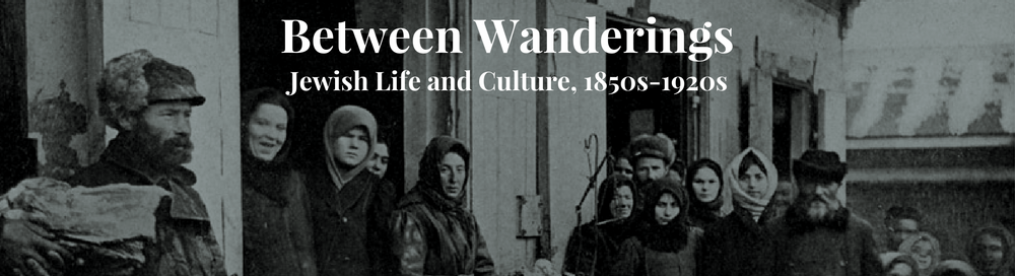

The day before Pesach on the East Side and on Riverside Drive.

By a Forverts reporter

The day before Pesach is the real holiday for our young people. Even earlier, two weeks before Pesach, they are already skipping elementary school and high school. Most have to help their mothers prepare for the holiday at home, while others must help their fathers at the pushcarts or the stores, where business is so frantic you can never have enough staff to satisfy all the customers.

And at home, there is also plenty to do: kashering, scrubbing, cleaning, fetching down the Pesach dishes, hanging new curtains on the windows, lifting old oilcloths from the floors and laying down new ones; making new little outfits for the children, shopping for all the Pesach foods — Can you now begin to calculate how many tasks a Jewish housewife is bombarded with at home on the day before Pesach?

Is it any wonder, then, that the day before Pesach, Jewish children are as pleased as can be and love the holiday wholeheartedly, no less than they love their “Easter vacation” from school?

In addition, Jewish children collect quite a Continue reading