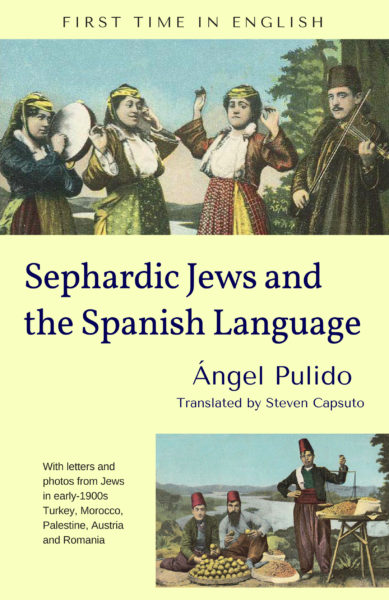

With letters and photos from Jews in early-1900s Turkey, Morocco, Palestine, Austria and Romania

In 1903, four centuries after Spain expelled the Jews, a Spanish senator launched a campaign to have his country reopen relations with their descendants, the Sephardic Jews. To promote the campaign, he wrote this classic book, now available in a new annotated translation.

Eager to let Jews speak for themselves, he devoted a third of the book to photos and letters from Sephardim in different countries, in which they describe their communities, synagogues, schools, families, literature and aspirations

They also wrote to him about Ladino—the Judeo-Spanish language that many of them still used at home and in worship. The book documents Sephardic life at a turning point: the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, when many young Sephardim were starting to reject the Spanish language that their ancestors had passed down from generation to generation since 1492.

Senator Pulido’s writings, lectures and organizing earned him the nickname “the Apostle of the Sephardic Jews.” His books on this topic continue to be cited frequently by scholars of Sephardic history.

In Spain, for nearly 400 years, the practice of Judaism was illegal and the country had all but forgotten the large and culturally vital community that had given it so much of its literature, music, science, and commercial success. But the descendants of the Jews that Spain expelled in 1492 never forgot their country, its language, or its Jewish variant, Ladino. One Spaniard, Ángel Pulido Fernández, recognized the importance of Jews to Spain, and the importance of Spain to the descendants of those who had been expelled. Though they had long since resettled in the countries of the Ottoman Empire and elsewhere, and were thriving as they had in Spain, Dr. Pulido sought to build bridges with the descendants of those who were cast out. Sephardic Jews and the Spanish Language is a fascinating historical document of one proud Spaniard’s attempt to right a terrible historical wrong and convince his politically and economically troubled country to embrace an integral part of its own heritage.