Rafael Cohen, a Turkish Sephardic Jew in Smyrna (now Izmir), sent letters about Jewish life in his city to the Spanish senator Ángel Pulido in the early 1900s. According to Pulido, Cohen was a language teacher who also worked for the Turkish Jewish newspaper El Messeret. Excerpts of his letters appear in Pulido’s second book about Sephardic Jews, published in 1905, whose title we could translate as Spaniards without a Country and the Sephardic Race.

Cohen writes that some Turkish Sephardim found it hard to believe that their language (Judeo-Spanish, also called Ladino, Judezmo, etc., which they wrote in the Hebrew alphabet) was a form of Spanish. But when he would hand them a newspaper from Spain, they generally found that even with their limited knowledge of the Latin alphabet, they could understand what they were reading.

In a letter dated September 8, 1904, he recalls:

Recently, one of them said to me, “Is it true that what we speak is a European language? Isn’t what we speak Judezmo?” I responded by handing him an issue of El Liberal. He laughed and began reading it and replied with great amazement, “This is one Spanish and ours is another…” Who could help feeling heartbroken at that reaction? I laughed ruefully and my heart ached at seeing a people, my people, speaking the most beautiful language without knowing, or rather without realizing, what they were speaking…

Cohen, something of a language purist, was one of the era’s Sephardim who advocated making Ladino more similar to what he called “true Spanish.”

In that era, Ladino was not taught at the Alliance Israélite’s two Jewish schools in Izmir, though those schools did often use the language in class. Cohen explained, though, that the private Jewish schools in Izmir did teach Ladino, while the city’s Protestant missionary schools (which had mostly Sephardic students) generally offered “standard” Spanish as a subject. In between the excerpts from Cohen’s letters, Pulido tells us that most Sephardic families in Izmir spoke Ladino at home in that era, even Jews who had attended schools that prioritized learning French (the Alliance schools) or English (the Church of Scotland Mission School of Izmir).

Regarding Sephardic newspapers in Izmir, Cohen writes:

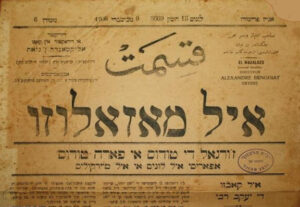

By 1908, there was another Ladino newspaper in Izmir: Aleksander Benghiat’s twice-weekly El Mazalozo, whose slogan was “A newspaper of everyone and for everyone.” It reportedly published for about six years.

Three newspapers are published in Judeo-Spanish in Rabbinic characters [Hebrew letters in Rashi print]. One of them, which you mentioned in your respected book, is La Buena Esperanza, which has existed for 34 years. It is edited by the venerable Mr. Hazan, a descendant of one of Andalusia’s most illustrious families, who distinguished themselves with their religious poetry.

The second is El Novelista (15 years), which was supposed to be published in French. However, because so few people here can read that language, its editor, Mr. Jacob Algranti, despite his perseverence, found it necessary to change the format and language of his daily paper (Note Bien) and today it is published in the gorgeous Spanish language.

The third is El Messeret (a Turkish word equivalent to Joy), which has existed for 8 years. Its editor, the very able and likeable Mr. Alexander Benghiat, manages the daunting task of publishing his newspaper in Turkish and in Spanish.

Regarding the preservation of Spanish as a Sephardic language and regarding Senator Pulido’s campaign for Spain to reestablish ties with Sephardic Jews in other countries, Cohen writes:

For the first time, after four centuries, I see a Spaniard communicating with one of Spain’s exiles, and having seen the fine responses you received from El Messeret and El Avenir, I feel ill suited to answer your questions. Even so, I take the liberty of telling you briefly that the preservation of the Spanish language among us should continue, despite all the persecutions; for if we forget it, we also forget the most important part of our history. As the indulgent people we have been, we always forgive those who wrong us. And as the faithful subjects that we are, it is impossible for us to become expatriots from the tolerant country of Turkey.

My eyes teared up as I read your letter addressed to the Spanish [i.e., Sephardic] press in Salonika. And I say clearly that there is no greater consolation for a Spanish Jew than to now be consoled by someone descended from people who were once spectators at the Inquisition’s public burnings.