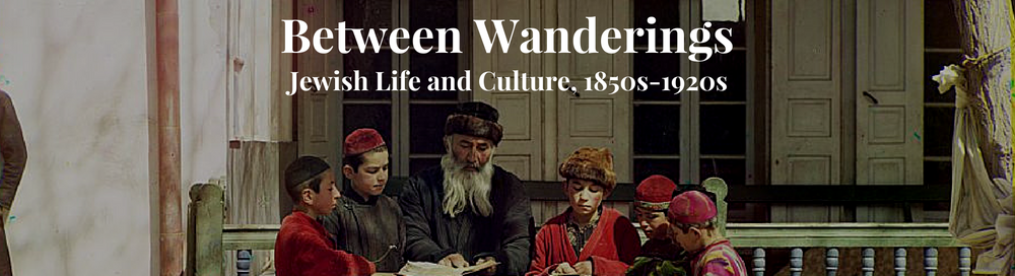

Auguste Widal’s Jewish writings from the 1840s and 1850s recall the traditions he grew up with in a French village in the early 19th century. Here are excerpts from “Sukkoth and a Betrothal.”

AUTUMN IS THE SEASON when Jewish holidays are most plentiful. September had returned with its cool, misty mornings and longer evenings, and I had not left Alsace. I was in Hegenheim, a village on the Swiss border just one league from Basle. There I would celebrate a holiday that had given me the loveliest memories ever since childhood: Sukkoth, also called the Feast of Tabernacles or of Booths. Hegenheim has had a large Jewish population since time immemorial, made up of cattle merchants, peddlers and clockmakers who all do business in and with Switzerland. A kind and honest clockmaker friend of Papa Salomon’s, little Aron, had offered me his hospitality. I arrived at his home as promised, the day before the holiday.

For the ancient Israelites, Sukkoth had both agricultural and historical meaning. Agriculturally, it marked the end of the harvests, the gathering of all the fruit of the trees and the vine. Also, presumably as a symbol of the harvest, the Law required people to bring a bundle of several plants to the Temple on the first day of the holiday. Historically, Sukkoth commemorates the Israelites’ wanderings in the desert, in memory of which they must live in temporary dwellings for seven days each year at this season. Hence Feast of Tabernacles or Booths.

All of this is obeyed rigorously in our countryside. Three days before the holiday, everywhere in the village, such bustle and activity! Men, lads and little boys all work on the sukkah or booth. In every courtyard, on every corner, in every little square, they build rustic shelters for themselves and their whole family. The foundations of these outdoor huts are four solid posts sunk deep into the ground. Staggered between these are poles that serve as the booth’s walls. The outside of each wall is covered in foliage and moss while on the inside, to block the wind, wide hangings of white fabric flutter to the ground on every side. The ceiling is a wooden trellis covered in fir branches laid in every direction, cut from neighboring forests. Local peasants, who know the Jewish calendar wonderfully well, have been coming to the hamlets every morning for days to supply the markets with these branches. The huts’ ceiling decoration is a matter of firm tradition. Chains of blue and yellow paper hang like drapes alongside wild rose branches with red hips, an attractive contrast to the greenery. Attached to the trellis are all the fruits of the season: pears, apples, grapes, nuts. Finally, dangling majestically not far from the door is an essential, infallible protection against all evil influences: a glorious red onion with rooster feathers sticking out of it as ornaments. No Alsatian Jew can remember any malign spirit, no matter how malicious it was, successfully intruding by day or night into a sukkah furnished with that precious bulb. In the middle of the ceiling, as close to the trellis as the other ornaments, triangles of gilded rods form the classic Star of David (mogen Doved), through which hangs a notched extender holding the seven-spouted lamp. Sometimes it rains but this frail structure is ready for anything: the removable doors can double as a roof. On rainy evenings, we huddle together even more happily in the improvised shelter amid the penetrating scent of fir trees. It is lovely to hear the rain on the sukkah’s greenery, adornments and coverings, as the flickering lamp lights a table laid with Alsatian abundance.

I recall that another Sukkoth guest was expected at my host’s home in Hegenheim: Papa Salomon’s fine son Shemele, and we all knew that the holiday was not the only reason for his journey. He was there to continue a marriage negotiation begun by the shadshen Ephraim Schwab. Shemele and Deborah, the daughter of wealthy Nadel, were to meet for the first time. If they liked each other, I could count on the curious spectacle of a traditional Alsatian Jewish betrothal ceremony.

The synagogue’s annual Sukkoth services have the same rustic tone as the joyous family gatherings in the sukkahs. The faithful arrive there in the morning. In their left hand, they carry a small basket or golden box containing a citron, and in their right hand, a long palm branch (lulef) to which a bouquet of myrtle is attached. This is all meant to evoke the holiday’s pastoral side. A vital moment in the ceremony comes after the hazzan (prayer leader) proclaims God’s bounty: all the congregants reply with a solemn Hosanna and walk throughout the synagogue shaking the palm branches, which strike each other audibly and release a wild aroma I cannot identify, redolent of the East.

On the first afternoon of the holiday, we followed custom and went visiting. First, Aron took me to Papa Nadel’s sukkah, which truly was a model booth. White and pink flowers spelled out this Bible verse about the holiday in Hebrew letters on each inner wall: “In booths shall ye dwell seven days.” Inside the shelter, seated royally between his wife and daughter, Papa Nadel was holding court.

He exclaimed as we entered, “Gentlemen, have a seat. There’s room here for everyone. Deborah, some glasses, some biscuits, some wine for these gentlemen!” …

[ . . . ]

The first day of Chol Hamoed (the semi-holy days of the holiday) arrived. This was the very day when my friend Shemele was expected at Aron’s. The weather was beautiful. A good autumnal sun shone on the horizon. The village was lively. Vehicles came and went, crowded with passengers. These were, as they say in the country, Chol Hamoed people, some going to neighboring villages and others coming to visit Hegenheim. Leisurely groups strolled or sat on wooden beams in the street to chat…

Scenes of Jewish Life in Alsace: Village Tales from 19th-Century France by “Daniel Stauben” (Auguste Widal) is available as a paperback and on many e-book platforms. See the Between Wanderings Books page for more information.

Scenes of Jewish Life in Alsace: Village Tales from 19th-Century France by “Daniel Stauben” (Auguste Widal) is available as a paperback and on many e-book platforms. See the Between Wanderings Books page for more information.

The book contains the following chapters, most of them set during Jewish celebrations and holy days in 1850s Alsace.

THE STORIES IN THIS BOOK:

Papa Salomon’s family

A fireside tale

Journey to Wintzenheim

A wedding

The feast and performers

Grief and mourning

Passover with the Salomons

Matchmaking on Shavuoth

The Days of Awe

Sukkoth and a betrothal

Purim

Chanukah and a strange tale