Below is the first chapter of Auguste Widal’s charming 1860 book Scenes of Jewish Life in Alsace, from a newly published English translation.

Widal grew up in Yiddish-speaking village communities in 1830s France, and his stories evoke a rural Jewish world that was vanishing quickly. The tales first appeared in the French Jewish magazine Archives Israélites starting in 1849. Under the pen name Daniel Stauben, he later revised and expanded them for a mainstream French magazine and for this book.

This new translation restores the Yiddishisms and Jewish wording that Widal deleted when reworking the stories for a general audience. The edition also adds illustrations by Alphonse Lévy, a 19th-century Alsatian Jewish artist whose drawings and etchings mesh perfectly with these tales.

CHAPTER ONE

IT WAS NOVEMBER OF 1856. An invitation from an old friend brought me back to Alsace, to scenes of village life I had known first as a small boy and which I now witnessed again years later with great emotion. As it happened, this short first trip gave me a chance to observe not only the curious characters who populate rural Jewish society in Alsace, but also some striking religious rituals: Friday’s and Saturday’s Sabbath observances, followed by a wedding and later a funeral. These episodes all happened in the order presented here. Imagination played no part in the many events I shall narrate.

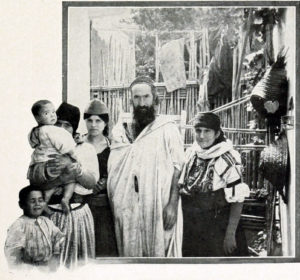

The village of Bollwiller, with its large Jewish population, lies a short distance from Mulhouse. Bollwiller is home to Papa Salomon, a handsome old man of seventy whose face exudes wit and warmth. Papa Salomon was to be my host, so I set out from Mulhouse to Bollwiller one Friday afternoon late enough to avoid reaching the village before around four o’clock. Arriving earlier would have disrupted their preparations for Shabbes—the Sabbath. On Fridays, women and girls in Jewish villages do double duty: the Laws of Moses forbid handling fire on the Sabbath, and so besides supper they must also prepare meals for the next day. As I still recalled, Friday mornings and afternoons are hard work, but the evening is one of those rare moments of rest when a Jewish community fully displays its true spirit. For these good folk, when the last rays of the Friday sun fade, so do all the worries, all the sorrows and all the troubles of the week. People say that the Danyes Vage (Wagon of Worries) travels through the hamlets each night, leaving the next day’s allotment of grief on poor humanity’s doorstep. But they also say that this wagon, a painful symbol of country life, halts on Fridays at the edge of each village and will not rattle into motion again until the next evening. Friday is everyone’s night of joy and ease. This is when the unhappy peddlers that you see all week with a staff in their hand and a bundle of merchandise—their whole fortune!—bending their back as they trudge up hills and down valleys, living on water and brown bread… On this evening, without fail, those peddlers will have their barches (white bread), their wine, their beef and fish. In summer, they will lounge in the doorway of their home in shirtsleeves and slippers, and in winter, they will sit behind a nice hot stove in a jacket and a cotton cap. On a Sabbath Eve, yesterday’s deprived peddler would not change places with a king.

Shabbes in the village.

I arrived in Bollwiller just at the Shabbes Shueh: the Sabbath Hour. That is what we call the hour before people go to synagogue. It is when girls touch up their grooming, a bit disarrayed by the day’s extra chores. It is also when fathers, fully dressed except for their frock coat, await the signal calling everyone to prayer. They use this free time to light the wicks of the seven-spouted lamp that all Jewish families have in Alsatian villages, made expressly for them as a fairly faithful replica of the famous ancient seven-branched lampstand. As I walked down the main street, I saw such lamps being lit in several homes. Suddenly, I heard the periodic banging of a hammer at different distances: three knocks on a shutter here, three knocks on a carriage gate there, struck by the shuleklopfer in ceremonial dress. This signal was as effective as the liveliest pealing of the loudest bell. Groups of men and women left at once for services in their Shabbes best, a garb specific to our Jewish villagers: The men wear loose black trousers that nearly cover their big oiled boots, a huge but very short blue frock coat with oversized lapels and a massive collar, a hat that is narrow at the base and widens towards the top, and a shirt of coarse but white fabric. The shirt bears two collars so tremendous that they block the face entirely, and so starched that these fine people must turn their body to look left or right. The women wear a dark gown, a large red shawl adorned with green palm leaves, and a tulle cap laden with red ribbons. A band of velvet takes the place of their hair, which has been carefully concealed since their wedding day. This finery is completed by a beautiful tefilleh (prayer book) printed in Rodelheim and bound magnificently in green morocco leather, which every pious woman Continue reading →