This blog will often feature personal narratives written by Jews in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. They’re like guest bloggers from our past, telling us their stories.

Today’s “guest” is immigration rights activist Mary Antin (1881-1949), who emigrated from Russia to Boston with her family in the 1890s. In her teens, she wrote a short book about her journey: From Plotzk to Boston (Boston: W.B. Clarke & Co., 1899), which she originally drafted in Yiddish. In the preface, she tells us:

In the year 1891, a mighty wave of the emigration movement swept over all parts of Russia, carrying with it a vast number of the Jewish population to the distant shores of the New World—from tyranny to democracy, from darkness to light, from bondage and persecution to freedom, justice and equality. But the great mass knew nothing of these things; they were going to the foreign world in hopes only of earning their bread and worshiping their God in peace. The different currents that directed the course of that wave cannot be here enumerated. Suffice it to say that its power was enormous. All over the land homes were broken up, families separated, lives completely altered, for a common end.

The emigration fever was at its height in Plotzk, my native town, in the central western part of Russia, on the Dvina River. “America” was in everybody’s mouth. Business men talked of it over their accounts; the market women made up their quarrels that they might discuss it from stall to stall; people who had relatives in the famous land went around reading their letters for the enlightenment of less fortunate folks; the one letter-carrier informed the public how many letters arrived from America, and who were the recipients; children played at emigrating; old folks shook their sage heads over the evening fire, and prophesied no good for those who braved the terrors of the sea and the foreign goal beyond it;—all talked of it, but scarcely anybody knew one true fact about this magic land. For book-knowledge was not for them; and a few persons—they were a dressmaker’s daughter, and a merchant with his two sons—who had returned from America after a long visit, happened to be endowed with extraordinary imagination…

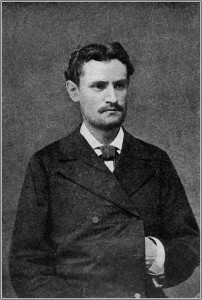

In her early thirties, Antin wrote a longer book—The Promised Land (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1912)—detailing the family’s life in the U.S. and her own Americanization.

It includes the following account of an issue faced by many Jewish immigrant couples: one spouse who wanted to cast off the trappings of religion and tradition, and one with more orthodox leanings. In this second book, Antin writes:

Israel Antin, Mary Antin’s father, who moved to America a few years before his wife and children (click to enlarge)

My father, in his ambition to make Americans of us, was rather headlong and strenuous in his methods. To my mother, on the eve of departure for the New World, he wrote boldly that progressive Jews in America did not spend their days in praying; and he urged her to leave her wig in Polotzk, as a first step of progress. My mother, like the majority of women in the Pale, had all her life taken her religion on authority; so she was only fulfilling her duty to her husband when she took his hint, and set out upon her journey in her own hair. Not that it was done without reluctance; the Jewish faith in her was deeply rooted, as in the best of Jews it always is. The law of the Fathers was binding to her, and the outward symbols of obedience inseparable from the spirit. But the breath of revolt against orthodox externals was at this time beginning to reach us in Polotzk from the greater world, notably from America. Sons whose parents had impoverished themselves by paying the fine for non-appearance for military duty, in order to save their darlings from the inevitable sins of violated Judaism while in the service, sent home portraits of themselves with their faces shaved; and the grieved old fathers and mothers, after offering up special prayers for the renegades, and giving charity in their name, exhibited the significant portraits on their parlor tables. My mother’s own nephew went no farther than Vilna, ten hours’ journey from Polotzk, to learn to cut his beard; and even within our town limits young women of education were beginning to reject the wig after marriage. A notorious example was the beautiful daughter of Lozhe the Rav, who was not restrained by her father’s conspicuous relation to Judaism from exhibiting her lovely black curls like a maiden; and it was a further sign of the times that the rav did not disown his daughter. What wonder, then, that my poor mother, shaken by these foreshadowings of revolution in our midst, and by the express authority of her husband, gave up the emblem of matrimonial chastity with but a passing struggle? Considering how the heavy burdens which she had borne from childhood had never allowed her time to think for herself at all, but had obliged her always to tread blindly in the beaten paths, I think it greatly to her credit that in her puzzling situation she did not lose her poise entirely. Bred to submission, submit she must; and when she perceived a conflict of authorities, she prepared to accept the new order of things under which her children’s future was to be formed; wherein she showed her native adaptability, the readiness to fall into line, which is one of the most charming traits of her gentle, self-effacing nature.

My father gave my mother very little time to adjust herself. He was only three years from the Old World with its settled prejudices. Considering his education, he had thought out a good deal for himself, but his line of thinking had not as yet brought him to include woman in the intellectual emancipation for which he himself had been so eager even in Russia. This was still in the day when he was astonished to learn that women had written books—had used their minds, their imaginations, unaided. He still rated the mental capacity of the average woman as only a little above that of the cattle she tended. He held it to be a wife’s duty to follow her husband in all things. He could do all the thinking for the family, he believed; and being convinced that to hold to the outward forms of orthodox Judaism was to be hampered in the race for Americanization, he did not hesitate to order our family life on unorthodox lines. There was no conscious despotism in this; it was only making manly haste to realize an ideal the nobility of which there was no one to dispute.

My mother, as we know, had not the initial impulse to depart from ancient usage that my father had in his habitual scepticism. He had always been a nonconformist in his heart; she bore lovingly the yoke of prescribed conduct. Individual freedom, to him, was the only tolerable condition of life; to her it was confusion. My mother, therefore, gradually divested herself, at my father’s bidding, of the mantle of orthodox observance; but the process cost her many a pang, because the fabric of that venerable garment was interwoven with the fabric of her soul.

My father did not attempt to touch the fundamentals of her faith. He certainly did not forbid her to honor God by loving her neighbor, which is perhaps not far from being the whole of Judaism. If his loud denials of the existence of God influenced her to reconsider her creed, it was merely an incidental result of the freedom of expression he was so eager to practise, after his life of enforced hypocrisy. As the opinions of a mere woman on matters so abstract as religion did not interest him in the least, he counted it no particular triumph if he observed that my mother weakened in her faith as the years went by. He allowed her to keep a Jewish kitchen as long as she pleased, but he did not want us children to refuse invitations to the table of our Gentile neighbors. He would have no bar to our social intercourse with the world around us, for only by freely sharing the life of our neighbors could we come into our full inheritance of American freedom and opportunity. On the holy days he bought my mother a ticket for the synagogue, but the children he sent to school. On Sabbath eve my mother might light the consecrated candles, but he kept the store open until Sunday morning. My mother might believe and worship as she pleased, up to the point where her orthodoxy began to interfere with the American progress of the family.

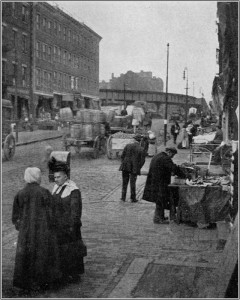

Harrison Avenue: the Heart of Boston’s South End Ghetto, around the corner from the Antins’ home (click to enlarge)

The price that all of us paid for this disorganization of our family life has been levied on every immigrant Jewish household where the first generation clings to the traditions of the Old World, while the second generation leads the life of the New. Nothing more pitiful could be written in the annals of the Jews; nothing more inevitable; nothing more hopeful. Hopeful, yes; alike for the Jew and for the country that has given him shelter. For Israel is not the only party that has put up a forfeit in this contest. The nations may well sit by and watch the struggle, for humanity has a stake in it. I say this, whose life has borne witness, whose heart is heavy with revelations it has not made. And I speak for thousands; oh, for thousands!

My gray hairs are too few for me to let these pages trespass the limit I have set myself. That part of my life which contains the climax of my personal drama I must leave to my grandchildren to record. My father might speak and tell how, in time, he discovered that in his first violent rejection of everything old and established he cast from him much that he afterwards missed. He might tell to what extent he later retraced his steps, seeking to recover what he had learned to value anew; how it fared with his avowed irreligion when put to the extreme test; to what, in short, his emancipation amounted. And he, like myself, would speak for thousands.

Both of Antin’s books are available online. At this writing, the links below are free downloads. The Project Gutenberg editions are good. I haven’t looked at the others.

- From Plotzk to Boston

- The Promised Land

NEXT WEEK’S POST: Jewish Schools in Palestine and Syria, 1870s-1900s: The Alliance Israélite Universelle.