Below is the first chapter of Auguste Widal’s charming 1860 book Scenes of Jewish Life in Alsace, from a newly published English translation.

Widal grew up in Yiddish-speaking village communities in 1830s France, and his stories evoke a rural Jewish world that was vanishing quickly. The tales first appeared in the French Jewish magazine Archives Israélites starting in 1849. Under the pen name Daniel Stauben, he later revised and expanded them for a mainstream French magazine and for this book.

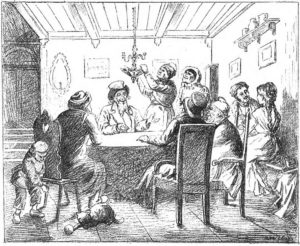

This new translation restores the Yiddishisms and Jewish wording that Widal deleted when reworking the stories for a general audience. The edition also adds illustrations by Alphonse Lévy, a 19th-century Alsatian Jewish artist whose drawings and etchings mesh perfectly with these tales.

CHAPTER ONE

IT WAS NOVEMBER OF 1856. An invitation from an old friend brought me back to Alsace, to scenes of village life I had known first as a small boy and which I now witnessed again years later with great emotion. As it happened, this short first trip gave me a chance to observe not only the curious characters who populate rural Jewish society in Alsace, but also some striking religious rituals: Friday’s and Saturday’s Sabbath observances, followed by a wedding and later a funeral. These episodes all happened in the order presented here. Imagination played no part in the many events I shall narrate.

The village of Bollwiller, with its large Jewish population, lies a short distance from Mulhouse. Bollwiller is home to Papa Salomon, a handsome old man of seventy whose face exudes wit and warmth. Papa Salomon was to be my host, so I set out from Mulhouse to Bollwiller one Friday afternoon late enough to avoid reaching the village before around four o’clock. Arriving earlier would have disrupted their preparations for Shabbes—the Sabbath. On Fridays, women and girls in Jewish villages do double duty: the Laws of Moses forbid handling fire on the Sabbath, and so besides supper they must also prepare meals for the next day. As I still recalled, Friday mornings and afternoons are hard work, but the evening is one of those rare moments of rest when a Jewish community fully displays its true spirit. For these good folk, when the last rays of the Friday sun fade, so do all the worries, all the sorrows and all the troubles of the week. People say that the Danyes Vage (Wagon of Worries) travels through the hamlets each night, leaving the next day’s allotment of grief on poor humanity’s doorstep. But they also say that this wagon, a painful symbol of country life, halts on Fridays at the edge of each village and will not rattle into motion again until the next evening. Friday is everyone’s night of joy and ease. This is when the unhappy peddlers that you see all week with a staff in their hand and a bundle of merchandise—their whole fortune!—bending their back as they trudge up hills and down valleys, living on water and brown bread… On this evening, without fail, those peddlers will have their barches (white bread), their wine, their beef and fish. In summer, they will lounge in the doorway of their home in shirtsleeves and slippers, and in winter, they will sit behind a nice hot stove in a jacket and a cotton cap. On a Sabbath Eve, yesterday’s deprived peddler would not change places with a king.

I arrived in Bollwiller just at the Shabbes Shueh: the Sabbath Hour. That is what we call the hour before people go to synagogue. It is when girls touch up their grooming, a bit disarrayed by the day’s extra chores. It is also when fathers, fully dressed except for their frock coat, await the signal calling everyone to prayer. They use this free time to light the wicks of the seven-spouted lamp that all Jewish families have in Alsatian villages, made expressly for them as a fairly faithful replica of the famous ancient seven-branched lampstand. As I walked down the main street, I saw such lamps being lit in several homes. Suddenly, I heard the periodic banging of a hammer at different distances: three knocks on a shutter here, three knocks on a carriage gate there, struck by the shuleklopfer in ceremonial dress. This signal was as effective as the liveliest pealing of the loudest bell. Groups of men and women left at once for services in their Shabbes best, a garb specific to our Jewish villagers: The men wear loose black trousers that nearly cover their big oiled boots, a huge but very short blue frock coat with oversized lapels and a massive collar, a hat that is narrow at the base and widens towards the top, and a shirt of coarse but white fabric. The shirt bears two collars so tremendous that they block the face entirely, and so starched that these fine people must turn their body to look left or right. The women wear a dark gown, a large red shawl adorned with green palm leaves, and a tulle cap laden with red ribbons. A band of velvet takes the place of their hair, which has been carefully concealed since their wedding day. This finery is completed by a beautiful tefilleh (prayer book) printed in Rodelheim and bound magnificently in green morocco leather, which every pious woman holds majestically against her abdomen.

Soon I found myself alone in the street. I would gladly have gone straight to my host’s house, but who could be so rude as to arrive at a home in a Jewish village on a Friday evening without going to synagogue first? So I ran there—a little ashamed at my lateness, I must confess. My host, waiting at the synagogue door, seemed to sense my embarrassment. He walked towards me, held out his hand and said the usual friendly “Sholem aleichem.”

“Don’t worry, my dear Parisian friend,” he added. “You’re not late at all. I knew you were coming, so I asked the hazzan (prayer leader) to be patient for a few moments and not chant the Boi B’sholem until your arrival, which I trusted would be soon.”

I was touched by this religious courtesy and thanked my host for it.

Like all houses in the village, Papa Salomon’s home consisted of a ground floor, used as a shop, and an upper level where the family lived. Narrow, almost vertical stairs—strewn with red sand and lit by a sort of branched tinplate candlestick on the wall—led us to a front door adorned with a large mezuzah. My host was a family man: his wife approached me, followed by two pretty daughters with very dark eyes and hair, and three vigorous lads. The whole brood laughed as they greeted me. In these Alsatian villages, people always laugh when welcoming guests, especially if they are afraid you will talk to them in French. This lets them be pleasant while stalling for time. The precaution was unnecessary in my case, since I am as proud as anyone to be a very correct speaker of our incorrect but lovely and evocative Judeo-Alsatian Yiddish jargon.

While Papa Salomon and his sons chanted the Malke Sholem and the rest of the family listened in religious silence, I ran my eyes over our surroundings. I gazed happily at all these objects that are much the same in every well-to-do Jewish home, objects I had seen often as a child and which had retained their ancient simplicity. There was the obligatory lamp hanging from the ceiling, and a red chintz tablecloth under which a bulge near the big leather armchair betrayed the presence of two barches (loaves of white bread) ordered for Friday evening. In one corner, a cistern with a copper basin rested on a green wooden base whose bottom, a cabinet, was reserved for storing the prayer book and some Talmudic volumes. One wall, the eastern wall, displayed a big, carefully framed sheet of white paper bearing the Hebrew word Mizrach (East). Mizrach signs are a common, thoughtful aid to visitors, letting them know which way they are commanded to face when praying to the Lord. Two prints also graced the walls: One depicted Moses with two rays of light shining from his forehead, with the tablets of the Law on his right and his classic staff on his left. The other portrayed the high priest Aaron, his chest and shoulders covered by the koshen and the ephod, his head wrapped in a priestly turban. A small mirror hung below an enormous deer head that served as a rack for the master’s hat or his cotton cap, depending whether he was at home or not.

After a meal of succulent Alsatian dishes, preceded and followed by prayers and psalms that Jews sing to traditional melodies, Papa Salomon told me that there would be a wedding the next Wednesday. His brother Yekel’s son was marrying the daughter of a parness[1] in Wintzenheim, a village located one league from Colmar.

“My brother Yekel, who you’ll see tomorrow,” he said, “will invite you to the wedding. But tonight in your honor, we’ll stay home. Do you still love stories around the fireside as much as you used to? Papa Samuel, who often spends Friday evenings here, will be with us tonight. Now there’s a storyteller! Ask my wife and children. It’s amazing how much he has read and, more impressively, how much he remembers! Ordinary tales, extraordinary tales, legends, adventures, enchantments… just tug his sleeve and it all tumbles out. But allow me one comment, my dear orech (guest). I know that you Parisians put little stock in the supernatural. Think what you like, but if Samuel tells us a tale of magic, don’t look skeptical. Otherwise he’ll stop and get angry. He’s proud in his way.”

Just then we heard a heavy tread on the steps. The door opened without anyone knocking.

“Gut Shabbes bay aynander!” said a hearty voice: Samuel was wishing us a good Sabbath.

He looked to be about fifty. Long side-whiskers framed his intelligent, rather plump face. Like so many men in the Alsatian countryside, Samuel did a wide range of jobs.

This worthy neighbor of Papa Salomon’s excelled equally in such varied and sensitive roles as substitute hazzan in the synagogue, nurse, storyteller, barber, matchmaker and messenger.

The new arrival, clearly aware of his status, settled in squarely and familiarly next to the master of the house.

“Samuel,” said my host without further preamble, “your timing is perfect. Since we can’t gamble tonight, you’ll tell us a manze (story), but a very good one to please this gentleman. This is a friend who lives in Paris.”

Samuel nodded a greeting without touching his hat.

“I don’t usually need coaxing,” he replied, “but let me think a bit. Let’s see! Now what could I tell you?”

His whole audience then launched a veritable assault on Samuel’s repertoire and erudition. The lady of the house clamored for the legend in which the Queen of Sheba travels through Bollwiller at certain times of year at one in the morning, dressed in white, hair fluttering, seated on a golden chariot that propels itself without a team.

Salomon’s two daughters begged Samuel to tell the tragic tale of little Rebecca, who unwisely glanced out her small kitchen window on a Saturday night. She saw the infamous Mohkalb[2] and heard its roar as it lurked beneath the outdoor sink, and she died of fright.

My host’s sons pleaded for the adventures of old Jacob, who got lost on his way to the Saint-Dié fair. At three in the morning, after walking all night, he found himself back where he had started the evening and was chased home by a gang of flame men, whose blazing fingers burned marks into his door as a sinister threat.

Papa Salomon asked for the story of notorious Nathan, known as Nathan the Devil, the terror and shame of the pious town of Grussenheim. Through his pacts with Hell, Nathan had conjured the sound of chimes in his granary in full view of everyone. He had made mysterious letters rain down from the ceilings and made tongues of flame shoot from the four walls of the parlor, which burned without being consumed.

“You’ve already heard all those tales or parts of them,” Samuel said, raising his head up high. “Let me tell you one that’s strange in quite a different way. I’ve never told it to anyone and I’ll ask you to keep it strictly between us, for my safety and for yours.”

“Before starting,” said my host, “take this glass of wine, Samuel, and make a toast with this gentleman.”

Then turning to the lady of the house, Papa Salomon said, “Yedele, call in the Shabbes goye (Sabbath maid) to pour oil in the lamp, fix the wicks and stoke the fire.” And resting his chin on both hands and his elbows on the still-open book of Psalms, he added, “Go ahead, Samuel. We’re listening.”

Samuel gulped down the wine, not without first reciting the required prayer, and readjusted his hat (which he had kept on in the house, like everyone else, of course). Then, in a patois that unfortunately loses much in translation, he began his tale.

NOTES (This blog entry omits some of the author’s notes)

[1] President of a Jewish congregation.

[2] A well-known legendary monster covered in eyes, also known as a Dorfthier (village beast).

Scenes of Jewish Life in Alsace: Village Tales from 19th-Century France is available as a paperback and on many e-book platforms. See the Between Wanderings Books page for more information.

Scenes of Jewish Life in Alsace: Village Tales from 19th-Century France is available as a paperback and on many e-book platforms. See the Between Wanderings Books page for more information.

The book contains the following stories, most of them set during Jewish celebrations and holy days in 1850s Alsace.

THE STORIES IN THIS BOOK:

Papa Salomon’s family

A fireside tale

Journey to Wintzenheim

A wedding

The feast and performers

Grief and mourning

Passover with the Salomons

Matchmaking on Shavuoth

The Days of Awe

Sukkoth and a betrothal

Purim

Chanukah and a strange tale