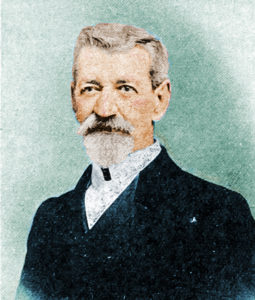

Lazar Ascher, president of Bucharest’s Sephardic Kehilla, president of the Bucharest Sephardic Jewish Primary Schools Society, early 1900s.

Today’s “guest blogger” from the past is Lazar (Lazaro) Ascher, a board member of several Sephardic organizations in Bucharest, Romania, in the 19th and early 20th centuries. He was a brother of Moscu Ascher, the noted Jewish philanthropist and educational reformer.

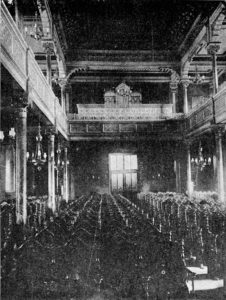

In this letter, Lazar writes about Bucharest’s “Spanish Jews” (Sephardim). The synagogue he describes is the Great Spanish Temple, also called Kahal Kadosh Gadol and Kahal Grande. That beautiful building, seen in photos below, stood at 10 Nedru Voda Street from the 1810s until the Iron Guard pogrom of 1941, just months before the Holocaust began.

You can find the complete 1904 letter and other correspondence from Sephardim of that era in Ángel Pulido’s book Sephardic Jews and the Spanish Language.

EXCERPTS FROM A LETTER TO

SENATOR ÁNGEL PULIDO, MADRID

[Translation from Spanish

© 2016 by Steven Capsuto]

Bucharest, February 16, 1904.

I was… overjoyed to learn that you are writing articles about the Spanish Jews, and that you want me to send photographs of our Synagogue and School. I’m glad to say I acted quickly and had photos taken of two parts of the Synagogue’s Moorish-style interior and of the facade. I also had pictures taken of our Jewish Community Schools for boys and for girls. I hope these are of use…

The Synagogue, built in 1817 and rebuilt in 1852, has 350 seats for men downstairs and 150 for women up in the gallery. The left and right galleries have entrances separate from the lower-level entry.

Our Community has had its Boys’ School since 1730. The school did not originally have its own space, but in 1817 four rooms were built for it on the grounds of the synagogue, and in 1894 the current building was erected. It is overseen by a five-man Committee. The Institute bears the name “School for Sons of the Spanish Israelite Community”…

The Spanish-Jewish Primary School for Boys. It was previously known simply as the Talmud Torah, which is what the sign over the door says. By 1904, this and the girls’ school were prestigious private elementary schools whose students attended free of charge, thanks to funding from the Halfon family foundation.

Our Community has had its Girls’ School since 1878. The sons and sons-in-law of the late Nissim and Lea Halfon donated 60,000 francs through their foundation, and the School is called the “Nissim & Lea Halfon Foundation School for Daughters of the Spanish Israelite Community.” The education is the same as at the Boys’ School. It teaches the national curriculum in Romanian, and Religion and the Bible in Spanish. Primary education lasts four years. The current building was erected in 1891 at a cost of 120,000 francs. The five-man Committee is the same as for the Boys’ School, but this Institution also has a Ladies’ Committee consisting of Mrs. Esther S. Halfon, wife of the President of our Community, Mr. Salomon J. Halfon; Mrs. Sarah S. Rizo, a co-founder of this Institute, daughter of the late Nissim and Lea Halfon; and Mrs. Thamara L. Ascher, my wife. This is a permanent Committee with lifetime appointments…

After all these centuries, the Spanish Jews preserve a striking number of old customs. For instance, we refer to parents, older siblings and aged relatives as Señor Padre, Señora Madre and so on. We address them with the formal “you” (not tú), and on holidays we kiss their hands. We address old men and old women who are not our relatives as Tío (Uncle) or Tía (Aunt). If a child falls down, people say to him la hora buena (I wish you well) or crescas como el piscadico en agua fresca (may you grow like a little fish in fresh water). When a child sneezes, they say crescas y enflorescas (may you grow and flourish). Even meals differ from those of our neighbors and closely resemble those of Spanish Jews in other places. For instance, they cook Almodrote (eggplant, with fat or oil, with cheese), Cucharicas (made by cutting an eggplant in two, scalding it, scooping out the inside and mixing this with egg and cheese, chopping the mixture with a wooden knife to keep it from turning black, stuffing it back into the skins and frying them in fat or olive oil). They also eat lentils on Fridays, which I imagine was an old Spanish custom because the great Cervantes says Don Quixote ate lentils on Fridays. Meatballs.

They bake treats with Spanish names such as pastellilos, pastel, bollos (even on the street, you hear people shout “Bollicos!”), quesadas, roscas (made with dough, flour, oil and egg) filled with alhasuo (a finely crushed mixture of nuts and crunchy cookies, with honey), marzipan, mustachudo (made with a small amount of flour, with sugar and wet almonds), and almendrada. Clearly I am no cook, so forgive the talk of food, but I wanted to show again how much my fellow Jews preserve your language and customs. Even our fellow Bucharesters call us simply “Spanioli,” Spaniards, as if we were members of the noble Spanish nation (if only that had been God’s will).

Now let me tell you a bit about my family. My Father was born here in 1797 and my Mother in 1804. In 1813, my Father inherited my Grandfather’s business, selling English fabric imported via Constantinople. My father was the first to import directly from England: cotton, thread and tools, filling entire ships. I was born in 1839, on March 8, and I learned Romanian, French and German. In 1857 my Father sent me to Dresden, where I graduated from the School of Business, and in 1860 I joined my Father’s business. My three older brothers already held responsible positions in the firm, and my Father gave me stock and I became a partner. In 1861 I began traveling to Austria, Germany, France, England, Switzerland, Belgium, Holland and Italy three times a year, so I would be here for a month and then away on business for three months. In 1863 my Father retired and left his four sons to carry on the company. In 1866 we lost my Mother and a year later my Father, may they rest in peace.

My Father left four identical wills, one for each son, written in Spanish in the Hebrew alphabet. The advice it contained included this: “You know, my dear ones, that our family’s watchword is ‘Honor before earnings.’ That was a legacy from my Father, your Grandfather, and now I leave it to you. I followed it most religiously. May you do the same, and so may the children of your children forever.” All of us did follow it, and still guard it like the eyes in our heads…

In 1872 I married a daughter of the late Lázaro de Mayo. The languages I know are Spanish (as you can tell), Romanian, French, Italian, German, English. I also have a reading knowledge of Hebrew.

My wife knows Spanish, Romanian, French, German and English, and plays the piano. I have three children. The eldest son, now 24, graduated from the local lyceum with great success and earned his diploma, and also graduated from the conservatory here, winning the top prize. Now he is at the University of Liege, where he passed every exam with distinction, the last of which granted him the title of Candidat Ingénieur avec distinction (Engineering Candidate with Distinction). He knows Spanish, Romanian, French, German and English, belongs to two music appreciation societies, and is much loved by all who know him, including some Spaniards he knows there named Moreno, who mistook him for a fellow Spaniard. Our second child is our 18-year-old daughter, Lucia, named after my mother, who has the honor of maintaining correspondence with your dear daughter. Our friend Mr. E. Bejarano [Rabbi Haim (Enrique) Bejarano] tells me they resemble each other greatly. She knows Spanish, French, German and Romanian, plays the piano and paints.

The third is León, aged 13. After completing all four primary-school years at our Spanish School, he is now in his second year at the local Business School. He knows Spanish, Romanian, French and German, and plays the piano. During my frequent travels, my greatest pleasure was to make the acquaintance of Spaniards in the hotel where I was staying and spend the evening with them. It was almost like being at home…

God speed your work. I remain at your disposal.

Sincerely,

Lazaro Ascher.

Regarding Ascher’s descriptions of Sephardic foods: Have any of you heard of frying cucharicas (as he states) instead of baking them? I see two possibilities: either this was a little-known Romanian version of the dish, or perhaps Ascher got it wrong. After all, he does say he’s no expert on cooking. Any thoughts?

The letter and some of the photos come from Ángel Pulido’s book, cited above. The other photos are from its 1905 sequel, Españoles sin patria y la raza sefardí. For this blog post, color was added to some images.

Bibliography

Dorian, Emil. The Quality of Witness: A Romanian Diary, 1937-1944. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1982. Includes an account of the bloody Iron Guard pogrom that destroyed numerous synagogues, including the Great Spanish Temple.

Popvici, Ileana, ed. Evreii din România în secolul xx: 1900–1920: fast și nefast într-un răstimp istoric: documente și mărturii. 2 vols. Bucharest: Editura Hasefer. 2003. A wonderful 1,100-page compilation of primary-source documents in Romanian from Romania’s Jewish communities in the years 1900–20. It includes considerable documentation of the Bucharest Sephardic community.

Pulido Fernández, Ángel. Sephardic Jews and the Spanish Language. My translation of this 1904 book, published in 2016 as the first title in the Between Wanderings Collection.

———-. Españoles sin patria y la raza sefardí. Madrid: Establecimiento Tipográfico de E. Teodoro, 1905. Pulido’s follow-up book includes further correspondence and more biographical details about people who appear in Sephardic Jews and the Spanish Language, and material from many other correspondents. Downloadable as a free PDF from Archive.org.

Sigaléa, Robert. De Bucarest à Sieugues: ou le chemin des écoliers et les sentiers de la peur. Félines: Editions du Fayet, 2003. An autobiography in French by one of Rabbi Haim Bejarano’s grandsons. It’s largely a World War II memoir, but includes an introductory section about his grandfather and information about the 1880s–90s renovation of the Great Spanish Temple, where Bejarano served as the congregational rabbi for many years.