New York’s first purpose-built Yiddish theater, the Grand, opened in 1903 and was bought by actor–producer Jacob Adler in 1904. While the People’s Theatre nearby was staging popular fare, Adler’s Grand Theatre often presented literary plays ranging from Shakespeare to the modern realist dramas of Jacob Gordin. [Photo from the book Jewish Immigrants in Early 1900s America: A Visitor’s Account.]

Today’s “guest blogger” from the past is a reporter for the Washington, D.C. Evening Star who wrote a feature in 1906 about foreign-language theaters in New York. In the excerpts below, the anonymous writer describes the plays and ambiance at three well-known Yiddish theaters of that era: the People’s, the Kalich (formerly the Windsor), and the Grand.

Except as noted, the photos and captions are not from the original article. Future posts about Yiddish theater will look at sources that are more specifically Jewish, but this colorful “mainstream” article, with its you-are-there feel, seemed like a good starting point.

It is conceivable the writer might be exaggerating slightly. (Did almost every production at the Grand really end after midnight?) But most of the information matches what I have read in Jewish materials, right down to the prompters at certain theaters who would read the whole script aloud during performances to remind the actors of their lines.

QUEER PLAYHOUSES

in New York That Are Patronized by Aliens

PLAYS IN FOREIGN TONGUES

Nightly Delight of Audiences of Different Nationalities

LEADING JEWISH THEATER

Where Dramas by Suderman

and Hauptman are Given Long

Before they Appear on Broadway

(Evening Star, March 10, 1906)

[The People’s:]

…In the very heart of the Bowery stands the People’s Theater, large and pretentious, with signs in Yiddish which proclaim that a melodrama is going on within. The place is always crowded, and there is no fashionable lateness about its audiences. They scramble in as soon as the doors are open. Stout matrons with children at their heels, pretty, dark-eyed Jewesses, long-bearded patriarchs, vegetable venders, ol’ clothes men—they are all there, they and their families. It is a good-natured, animated crowd. As the theater fills there is a hum, then a buzz, and presently the gallery begins shouting and stamping its impatience.

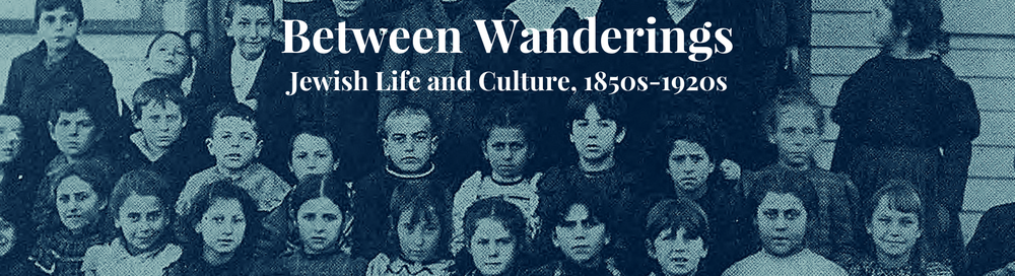

Bessie Thomashefsky—half of the famous Yiddish theatrical couple of Boris and Bessie Thomashefsky—was beloved for her performances in musicals and comedies at the People’s Theatre. Here she plays the title roles in Dos Grine Vaybl, oder Der Yidisher Yenki-Dudl (The Greenhorn Wife, or The Jewish Yankee Doodle) and Der Griner Bokher (The Greenhorn Boy), both from 1905. [Photos and caption from the Jewish Immigrants book.]

The melodramas offered are like our own thrillers of the “Two Little Vagrants” order, but the scenery and costumes are cruder. For instance, the small boy who holds up the moon wobbles till that planet describes circles not mentioned in astronomy. And when the play rises to a climax the moon is occasionally thrust aside entirely, and the eager, excited face of the boy shines down instead.

Scene from A Father’s Love, People’s Theater (Yiddish). [Photo and caption from the original newspaper article.]

Though the plays are acted In Yiddish, the scenes are laid in New York—Ellis island, the Ghetto, the wharves of the East river. Many of the characters are drawn from every-day life, East Side cantors, rag-pickers or emigrants.

The bill is changed every night, and the plays are often put on with but a single rehearsal, the actors relying upon the prompter, who sits in a shell by the footlights and reads the whole play in a voice audible to the furthest corner of the house, a fact that does not seem to upset in the least the rapt attention of the audience.

And what an audience it is! It is never still a moment. It weeps openly at the heroine’s wrongs… It rises to hiss the villain or applaud the hero, and yells… “Shame!” when the flinty-hearted father turns his child out of doors.

The acting is usually good. If it isn’t, the gallery is loud in its criticism.

There are many little by-plays not scheduled on the bill. Often a newsboy or bootblack saves his pennies and brings to the theater a huge bunch of flowers (sometimes wrapped in newspaper), which he throws to the leading lady, at which exhibition of gallantry the cat calls of the gallery rise to shrieks, and pretty Miss Lobel has to bow her thanks again and again.

Between the acts the whole house is astir. The theater is even a more stylish place for visiting than a sidewalk or doorstep. Friends in the dress circle recognize friends in the balcony, and greetings are exchanged, often in English.

“Where’s David Jabrowsky?” some one calls up to the gallery.

“He ain’t here tonight,” a voice shrills back. “He’s got de mumps!”

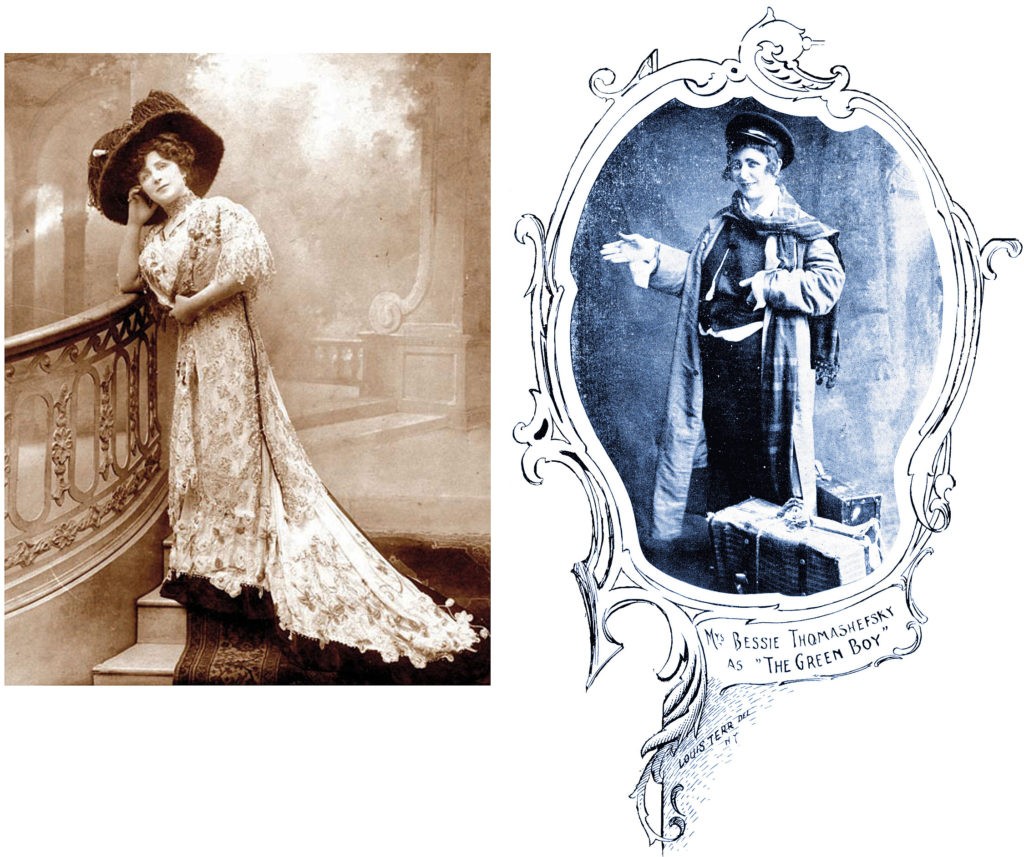

Top: “Jews at a Yiddish theater.” Bottom: “The same Jews at an English theater.” From the Yiddish satiric weekly Der Groyser Kundes (The Big Jokester), circa 1910s. Author Stefan Kanfer included this cartoon in his 2006 history of the American Yiddish theater, Stardust Lost.

The most intimate family matters are discussed. Any one who listens may know that the Stroskys have got a new baby, and Rachael Oldstein has achieved a fine hat “offen the lady” where she works…

When the play is done the audience jostles into the street to open-air booths, where hot tamales and sandwiches are sold, and those who can afford it stand munching under the street lamps, their faces smeared and happy. And this marks the end of the evening’s entertainment.

[The Kalich:]

The great Yiddish-theater and Broadway actress Bertha Kalich, seen here on sheet music for a song that was played nightly in the theater that bore her name. [Photo: U.S. Library of Congress, Hebraic Division.]

Another Yiddish theater is the Kalich, named after Madame Bertha Kalich, who used to play there before she ascended among the stars of Broadway. Intense pride is taken in the progress of this gifted woman, and there is not an ambitious actress on the Bowery but hopes to follow in her footsteps.

The Kalich Theater is Hebraic to a degree. On the drop curtain is a harrowing picture of the persecution of the Jews. Above it are panels representing Moses with the tablets of the law, Solomon deciding between the two mothers, and Elijah ascending in his chariot.

Hebrew [i.e., Jewish] comedies and melodramas are given, as are also the plays of Ibsen. Some of the costumes are an odd mixture of American and old country styles. All of the players are foreign born, and most of them received their dramatic training in Russia.

[The Grand:]

Jacob Adler in The Merchant of Venice, 1890s or 1900s. Adler portrayed Shylock in Yiddish at the Grand and elsewhere for years, sometimes in productions where the rest of the cast acted in English. His Shylock was different from others of that era: defeated but not intimidated at the end of the play, he made his final exit with his head high, a vision of dignity, contempt and defiance towards his non-Jewish enemies. [Photo: Folger Shakespeare Library.]

Probably the leading Jewish theater in America is Jacob Adler’s, on Grand Street. The audience here differs vastly from that of the People’s and the Kalich. It is at once more aristocratic and cosmopolitan, for the fame of Adler’s “Shylock” draws people of every nationality. Plays by Suderman and Hauptman are given there long before they are produced at Broadway theaters.

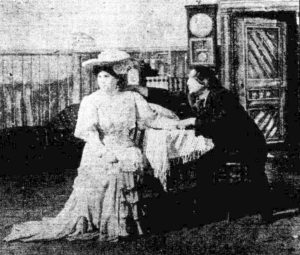

Jacob Adler and leading lady in Abnormal Man. [Photo and caption from the original newspaper article.]

No matter how long, the plays are never cut. It is seldom that a performance ends before 12 o’clock. Even then the people do not seem anxious to go home, but linger applauding in the aisles, with cries of “Adler!”

Even more interesting than these classic plays are the folk dramas of Jacob Gordin, the theater’s own playwright. In these one gets glimpses of curious interiors of the old world, and characters not known to our American stage—the Russian schoolmaster, with his tall fur hat, the quaintly loquacious watchmaker and his wife, bakers, sledge drivers, toy makers, all in the costumes belonging to their trade.

The property room of this theater is a delight. Everything in it is real. Brass bowls and candlesticks from Odessa, earthenware lamps from Hungary, and queer long-stemmed pipes such as the peasants of Poland use. Even the square legged tables and chairs, the porcelain stove, the tall clock with a decorated face came from lands across the sea. Perhaps this is one reason why the plays given in the Grand Street Theater have such convincing atmosphere…

_________

The rest of the article describes Italian and Chinese theaters in New York.

_________

Additional reading elsewhere online:

Memoirs of the noted actress BERTHA KALICH (1874-1939) are being serialized on the Digital Yiddish Theatre Project website, translated from Yiddish into English by Amanda (Miryem-Khaye) Seigel. The first three installments are now online.