The ideal for women of my race is education, instruction, and raising girls to be good housewives. In Bosnia, all the young [Sephardic] women now speak three languages: Spanish, German and Slavic, which is the national language. At convent schools, they learn to do beautiful handiwork. A nun in Sarajevo told me that her Jewish students are the most diligent, clever girls she teaches, and they learn German easily. Feminism has not yet reached us here; man is what he is: the king of the world.

—Micca Gross Alcalay, 1904

This blog often presents newly translated first-person accounts of Jewish life in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Today’s “guest blogger” from the past is Marietta “Micca” Gross Alcalay, a Sephardic Jew born in Bosnia in the 1860s or 1870s. She lived most of her adult life in Trieste, Austria (now Italy). Below, she will tell us about facets of everyday life that history books often skip: greetings, songs, children’s games, a wedding tradition, and attitudes towards women.

Cultured and well-read, she had friends and relatives in many Sephardic communities in Eastern Europe and the Mediterranean. In 1904, when Spanish author Ángel Pulido began research for a follow-up to his book Sephardic Jews and the Spanish Language, Alcalay became his research assistant.

They never met, but they exchanged long daily letters in Spanish, delighting in this or that newfound piece of information about Sephardim. Unlike some of his correspondents, she wrote in a direct style that let her personality shine through. (“I’m still waiting for a reply from Sarajevo about my question,” she once wrote. “I think they must be searching high and low to find an intellectual.”)

Pulido urged her to write to him about the customs of Sephardic women. Below are excerpts of her replies, which offer a window into gender relations in that era.

You’ve set me a rather hard task, telling you about Sephardic women… I must duly acknowledge their moral virtue: Adulterous women, fallen girls, are as rare as white flies. How could it be otherwise, since right from girlhood we are warned constantly about the sin and horror that prostitution brings? The second virtue is love of home, of family, and especially charity and love for our fellow man. My good father used to tell me, “Daughter, the poor man and the beggar, all share the same religion. Give to anyone who holds out a hand to you.” Sephardic women deserve every praise for their domestic virtues, for they are very capable and thrifty.

* * *

You asked about our more affectionate feminine customs. First, I’d like to tell you about everyday blessings. A young woman typically greets an older woman by saying Beso sus manos (“I kiss your hands”). If the younger woman is unmarried, the old woman blesses her by saying Dicha y suerte buena tengas (“May you have happiness and good luck”). If she is married, Tures dichosa (“May you stay happy”) or just Dichosa y alegre (“Happy and joyful”). If she is pregnant, Bien parido de un hijo (“May you have a healthy boy”). People love daughters after we’re already born: “forza maggiore,” as the Italians say—an unavoidable Act of God.

The most moving event is on the eve of a wedding. In the home of the young woman, or bride, female professional singers gather with their tambourines and sing this song, which draws many tears if the girl will be leaving to live with her husband abroad, as I did:

“Hija antes que te vayas,

mira bien y para mientes,

por los caminos que irás,

no hay hermanos ni parientes.

A los ajenos aparienta,

no te dés á borecer,

hija del buen parecer.”

“Daughter, before you go

Look carefully and pay attention.

On the roads you will travel

There are no siblings or parents.

Make family of the strangers,

And do not give yourself over to hatred,

O lovely daughter.”

It has an Arab melody that is as sad as the lyrics, but it is a much-needed admonition to the girl.

* * *

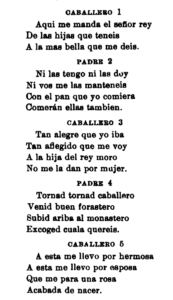

I don’t know if the song below will interest you, but when I was young, the older girls would sing it as part of a game. And there was no lack of poetry in the time and place where we played it, in what I like to call the “preparandum” for marriage. After all, who among us could doubt that someday, a “knight”—or the nearest equivalent—would come to ask for the hand of the “daughter of the Moorish king”? We used to play “I was Sent Here by My King” in summer, in the gardens. One girl would be chosen as the knight and another as the protective father, and the rest of us would sit in a row in the small grove that served as our “cloister.” With much grace, we would hear the Knight sing:

KNIGHT – Stanza 1:

I was sent here by my king.

Your prettiest daughter I’m to bring

Away to wear my wedding ring.

FATHER – Stanza 2:

Not mine to give, nor yours to take

Though I’m the one who keeps them fed

Before I’d ever let them starve

I’d give them my own bread.

KNIGHT – Stanza 3:

I cannot smile, I cannot sing,

My heartbreak I can’t hide;

For the daughter of the Moorish king

Shall never be my bride.

FATHER – Stanza 4:

Return, good knight

And at your ease

Go to the cloister

And choose the bride you please.

KNIGHT – Stanza 5:

I choose this beauty as my wife

I pick this prize to share my life

For I have found a joy apart:

A newborn rose has pierced my heart.

Then the girl chosen as the bride was adorned with flowers, and we celebrated the wedding with fruit and baked treats. When I remember how longingly the girl playing the father would call for the knight to take one of the daughters, I laugh, because that’s how it is in real life: “Return, good knight,” followed by “And don’t ask for too big a dowry.”

I translated these letters from the book that Micca Gross Alcalay helped to research: Españoles sin patria y la raza sefardí (Spaniards without a country and the Sephardic race). The original Spanish edition can be downloaded from Google Books as a PDF.

Alcalay died young, in her thirties, on May 18, 1905, shortly after the book’s publication. She wrote many pages of material about the Sephardic communities of Trieste and Bosnia and about other topics for that book. I hope to translate portions for a future blog entry.

(Translations ©2016 by Steven Capsuto. My annotated English edition of Pulido’s previous book about Sephardim is available as a photo-illustrated paperback and in major e-book formats.)